This article first appeared in the Christian Research Journal, volume 40, number 02 (2017). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For more information about the Christian Research Journal, click here.

SYNOPSIS

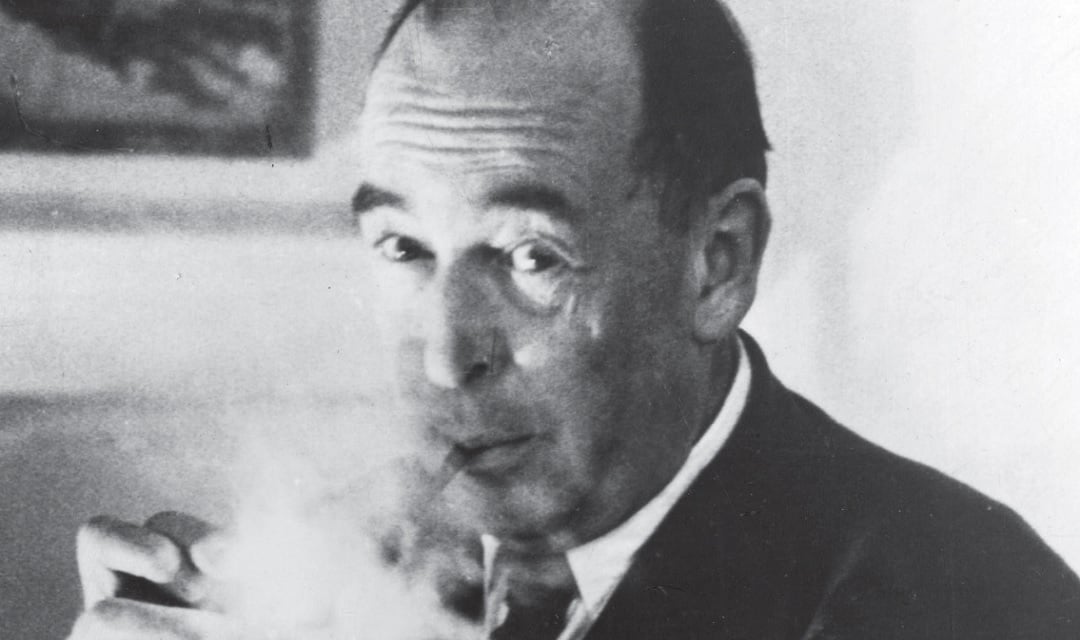

Many have argued about the validity of C. S. Lewis’s apologetic arguments. (They are sound.) This essay will look at Lewis as a practical role model for winsome Christian apologists. What made him a good one? He understood the evangelistic situation we face in the modern world, in which sin and true moral guilt are missing concepts and the biblical worldview a foreign country to most people, yet he was not tempted to alter the gospel to make it more palatable to the evolving audience. He understood how to communicate abstruse ideas and linear arguments in a way that normal human beings can follow. He understood that good arguments are a necessary but not a sufficient condition of an effective apologia. He knew how to make his arguments meaningful by calling imagination to the aid of reason and by putting them in the context of a life of loving service. This combination of features made him the greatest apologist of the twentieth century. The conclusion for us is to “go thou and do likewise.”

Many scholars have taken pen in hand to discuss the validity of C. S. Lewis’s apologetic arguments. I have been one of them.1 But here I will address what we can learn practically about apologetics as Christian ministry from Lewis’s approach to defending the faith. A fresh look at his approach could be useful to both evangelists and apologists in the twenty-first century.

EVANGELISM

C. S. Lewis did not talk a lot about evangelism. He just did it. He often did it indirectly, but it got done. There is no direct appeal for conversion in the broadcast talks that became Mere Christianity, but there is an exposition of the Christian faith designed to elucidate its attractiveness as an answer to the problems of fallen man as well as to underscore its truth. And conversion was often the result, as famously with Charles Colson. But while Lewis’s evangelism may have been indirect, it was not unintentional. When Sherwood Eliot Wirt of the Billy Graham Association asked whether he would say that the aim of his writing was “to bring about an encounter of the reader with Jesus Christ,” Lewis replied, “That is not my language, yet it is the purpose I have in view.”2

Lewis did not feel he had the gifts for the “direct evangelical appeal of the ‘Come to Jesus’ type,” but he thought those who could do that sort of thing should “do it with all their might.”3 Lewis practiced evangelism by writing, speaking on the radio, speaking for the RAF in World War II, and in personal letters and other contacts. His commitment to evangelism and the price he paid for it at Oxford are covered brilliantly in David Mills’s book The Pilgrim’s Guide: C. S. Lewis and the Art of Witness, especially in the late Chris Mitchell’s essay, “Bearing the Weight of Glory.”4

Diagnosis of Sin

Through all of these experiences, Lewis came to have a good understanding of the problems with doing effective evangelism in the modern world. He noticed, “The greatest barrier I have met is the almost total absence from the minds of my audience of any sense of sin.…We have to convince our hearers of the unwelcome diagnosis before we can expect them to welcome the news of the remedy.”5 This was a new situation without precedent in church history. “When the apostles preached, they could assume even in their Pagan hearers a real consciousness of deserving the Divine anger….Christianity now has to preach the diagnosis—in itself very bad news—before it can win a hearing for the cure.”6 This means more work for the evangelist, who can no longer do his job effectively without help from the apologist. There is no hint of the idea that we have to adjust the message to make it more palatable to this new, tougher audience. Rather, we must gird up our loins and do the work required to gain a hearing for this unwelcome diagnosis and the joyous cure that can make sense only when the sick accept that diagnosis.

APOLOGETICS

The evangelist increasingly needs help from the apologist because the diagnosis is no longer self-evident; it is no longer self-evident because the Christian worldview is now a foreign country to most people. They must be persuaded (the apologist’s job) to try the experiment of looking at the world and their own hearts very differently from the way they habitually do, if they are even to understand the relevance of the gospel to their lives, much less accept it as good news and truth. The liberal approach to this dilemma is to try to accommodate the gospel to the modern (now, postmodern) worldview, to make it more palatable to the audience that exists. But this approach begs the question. If the gospel is not true, then it is not good news for anyone; and if it is true, then the modern worldview must at points be false. Lewis never seems to have been tempted by the liberal cop-out. He was prepared to accept the challenge that, in order to present the good news today, we must convince people that not only their behavior and their beliefs but also their thinking have been mistaken at crucial points.

Apologetics is how we do this job. It is the defense of the faith, that branch of theology that asks of the gospel, “Why should we think it is true?” It is the one branch of theology in which Lewis was recognized as an expert. His broad and deep learning, which kept him in touch with the best products of both the human mind and heart; his rigorous training in logic and debate by W. T. Kirkpatrick; and the fact that his own conversion was facilitated by reasoned arguments from Chesterton and Tolkien7: all these factors combined to make Lewis one of the greatest apologists we have seen. What can he tell us about apologetics as a form of practical theology?

The Need for Apologetics

Apologetics is a biblical mandate: “Sanctify Christ as Lord in your hearts, always being ready to make a defense to everyone who asks you to give an account for the hope that is in you” (1 Pet. 3:15). The word translated “defense” is apologia, from which comes the English apologetics. It is a courtroom term for the kind of reasoned case a lawyer makes in defense of his client. Lewis was in tune with a number of the reasons why that mandate exists.

One is the very nature of the faith to which the gospel calls us. Many modern people, Christians included, treat faith as a strange mystical way of knowing that is unconnected to reason or evidence. It is a zero-sum game in which the more reason and evidence you have, the less of a role is left for faith to play. The New Testament, however, knows nothing of such ideas. For the biblical writers, faith is simply trust, and salvation is granted to people who put their personal trust in Christ as God’s Messiah. You could conceivably have that trust for good reasons, bad reasons, or no reasons. It is better to have good reasons. Luke says that Jesus offered “many convincing proofs” of His resurrection (Acts 1:3), and early preachers such as the apostle Paul were constantly giving reasons and evidence to back up their message. So we could say that apologetics is based on a biblical precept (Peter’s command), biblical precedent (the apostles’ example), and a biblical principle (that the gospel is truth that should be addressed to the whole person, including the mind).

Lewis accepted this biblical perspective fully, as shown by his teachings on the nature of truth,8 his practice of apologetics, and is direct statement: “My faith is based on reason.…The battle is between faith and reason on one side and emotion and imagination on the other.”9 It is not that emotion and imagination are inherently opposed to faith (one factor leading to Lewis’s conversion was the “baptism” of his imagination by George MacDonald), but that in fallen human beings, they often are opposed to it. When reason appears to be opposed to faith, on the other hand, this opposition is illusory, because if the gospel is true, then true reason must support it. We practice apologetics in our evangelism then because of the nature of the gospel as truth and the nature of human beings as whole people who have minds as well as hearts that need to be reached.

The nature both of the gospel and of human beings makes apologetics a necessary part of theology for every generation. The times in which we live can make the need even more pressing. Lewis lived in such times, and the needs he saw have not diminished to the present. A skeptical age will have its effects even on people raised in Christian homes. Lewis describes those effects graphically. He wrote that “Skeptical, incredulous, materialistic ruts have been deeply engraved in our thought.”10 As a result, even committed Christians have moments when Christian truth claims look implausible. In such an age, apologetics is essential equipment for believers wanting to preserve and strengthen their own faith as well as to proclaim it to others.

The ruts have not only been dug; they are systematically reinforced. Lewis’s observed ruts have been worn deeper, and new ones have been added. Our age remains as skeptical as Lewis’s was, and to that challenge, we have now added the ruts of pluralism and its offspring, multiculturalism. Neither evangelism nor Christian nurture can be conducted effectively without help in navigating around, smoothing out, or bridging over those ruts. Therefore, Lewis’s advice is even more pertinent today than it was when he gave it: “To be ignorant and simple now — not to be able to meet the enemies on their own ground — would be to throw down our weapons, and to betray our uneducated brethren who have, under God, no defence but us against the intellectual attacks of the heathen. Good philosophy must exist, if for no other reason, because bad philosophy needs to be answered.”11

Practical Apologetics

There are a number of strong arguments pointing to the truth of the Christian faith. But Lewis realized that having good arguments is not enough. We also need to influence the general climate of opinion. In a secular age, unexamined attitudes and ideas influence our minds in ways that do not affect the validity of the reasons we have for believing in God, but may affect their plausibility. For example, Lewis’s protagonist Ransom insists that “what we need for the moment is not so much a body of belief as a body of people familiarized with certain ideas. If we could even effect in one per cent of our readers a change-over from the conception of Space to the conception of Heaven, we should have made a beginning.”12 How we imagine the world influences how we think about it, the kinds of arguments to which we will be drawn, and the kind of conclusions we will draw from them.

Lewis’s arguments were effective partly because he knew that more than argument was needed. They were supplemented by attempts to imagine what the world would look like if Christianity were true as well as by arguments not directly about apologetic issues. Lewis wanted Christians to pursue intellectual excellence in general in order to create a situation in which people were not so unused to seeing things from the perspective of the Christian worldview as they were already becoming in his generation. “What we want,” he said, “is not more little books about Christianity, but more little books by Christians on other subjects.”13 When the best available treatments of art, literature, politics, philosophy, ethics, and science all speak as if Christianity is true, then when the time comes to make the case for its truth directly, a receptive audience will have been created. We still have much work to do here.

Lewis was also effective because he was winsome and intelligent. Here is a passage in which he slyly turns the tables on the skeptics. As an atheist, Lewis had to believe that the great majority of the human race was wrong. “When I became a Christian,” he remarks, “I was able to take a more liberal view.”14 Here he steals a favorite buzz word from his opponents, “liberal,” and a favorite stance, tolerant openmindedness, and stands them on their heads to be used against them. Lewis makes his point, but doesn’t rub it in; he makes it and moves on. We could learn much from him in manner as well as message.

Lewis had a unique capacity to express the most profound Christian ideas that apologetics defends in language normal people can understand. This was a gift, but it is also a skill that can be cultivated. Lewis wrote, “It has always seemed to me odd that those who are sent to evangelise the Bantus begin by learning Bantu while the Church turns out annually curates [clergymen] to teach the English who simply don’t know the vernacular language of England.”15 He also stressed that you do not really even understand a concept if you cannot translate it into the vernacular. He thought such translation ought to be compulsory for every ordination examination.16 It was good advice for the apologist as well as the pastor and the evangelist.

The Final Apologetic

Lewis would have agreed with Francis Schaeffer that “the final apologetic” is a life lived as if the Christian message were true.17 Lewis noted, “If Christianity should happen to be true, then it is quite impossible that those who know this truth and those who don’t should be equally well equipped for leading a good life.”18 Christians so equipped should indeed be combining a life that exhibits human thriving from the application of Christian truths with a sacrificial commitment to showing the love of Christ. Without this “final apologetic,” no argument will be compelling to people from whom we are asking not just intellectual assent but life commitment. To some, it will be the only argument that can speak. Lewis wrote, “When a person…has lost faith under so very great and bewildering a trial, no intellectual approach is likely to avail. But where people can resist and ignore arguments, they may be unable to resist lives.”19

The final point is that apologetics is a form of spiritual warfare, not without casualties. The best way to be one of those casualties is to ignore the danger. Lewis did not. He realized that “nothing is more dangerous to one’s own faith than the work of the apologist. No doctrine of that faith seems to me so spectral, so unreal, as the one I have just successfully defended.…For a moment, you see, it has seemed to rest on oneself.”20 Therefore we must reckon seriously with the fact that intellectual preparation is necessary but not enough. The apologist must be a person who walks with the Lord in such a way that he cannot forget on Whom things truly rest.

ENCOUNTERING CHRIST

Why do we need apologetics? We live in a world filled with people who think like Prince Caspian’s Trumpkin: “I have no use for magic lions which are talking lions and don’t talk, and friendly lions though they don’t do us any good, and whopping big lions though nobody can see them.”21 The only cure for that attitude was for Trumpkin to meet Aslan. We are all constitutionally unbelieving Narnian dwarfs. “You see,” said Aslan, “They will not let us help them. They have chosen cunning instead of belief. Their prison is only in their own minds, yet they are in that prison; and are so afraid of being taken in that they cannot be taken out.”22

Only the Holy Spirit can take us out of those internal prisons so we can hear the evidence for Christ and respond to it with faith. He wants us to be ready to present that evidence so He can do so. Lewis’s friend Austin Farrer put it well: “Though argument does not create conviction, the lack of it destroys belief. What seems to be proved may not be embraced; but what no one shows the ability to defend is quickly abandoned. Rational argument does not create belief, but it maintains a climate in which belief can flourish.”23

Lewis, in other words, well understood that the goal of apologetics is not just to win arguments. It must be what he allowed to Wirt was the goal of all his writing: “To bring about an encounter of the reader with Jesus Christ.” The purpose of apologetics is to help people channel the shock of that encounter into a serious consideration of the claims of Christ. It is to ensure that this encounter is with the Christ of history, and not a counterfeit, that it is an encounter of the whole person with that Christ, and that the faith we hope people will put in Him will be a rational, well-considered, and well-grounded faith. It is to help believers whose faith is more superficial grow into that well-considered and well-grounded faith themselves.

The goal is not just to win arguments. It matters little that we persuade people to believe that theism is true in the abstract unless this enables them to meet God. Lewis reminds us, “We trust not because ‘a God’ exists, but because this God exists.”24 We want to get people to the place where “what would, a moment before, have been variations in opinion, now become variations in your personal attitude to a Person. You are no longer faced [simply] with an argument which demands your assent, but with a Person who demands your confidence.”25 For if indeed they can be brought to see the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ, they will be ready to say with Orual (Till We Have Faces), “You are yourself the answer. Before your face questions die away.”26

Donald T. Williams, PhD, is R. A. Forrest Scholar at Toccoa Falls College and past president of the International Society of Christian Apologetics. His most recent book is Deeper Magic: The Theology behind the Writings of C. S. Lewis (Square Hollow Books, 2016). He blogs at http://thefivepilgrims.com/.

NOTES

- E.g., in C. S. Lewis’s Apologetics: Pro and Con, ed. Gregory Bassham (Leiden, NL: Brill/Rodopi, 2015), 171–89, 201–4.

- C. S. Lewis, “Cross Examination,” in God in the Dock: Essays on Theology and Ethics, ed. Walter Hooper (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1970), 262.

- C. S. Lewis, “Christian Apologetics,” in God in the Dock, 99.

- Christopher W. Mitchell, “Bearing the Weight of Glory: The Cost of C. S. Lewis’s Witness,” in The Pilgrim’s Guide: C. S. Lewis and the Art of Witness, ed. David Mills (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 3–14.

- C. S. Lewis, “God in the Dock,” in God in the Dock, 243–4; cf. “Christian Apologetics,” 95.

- C. S. Lewis, The Problem of Pain (New York: MacMillan, 1967), 43.

- Donald T. Williams, “G. K. Chesterton, The Everlasting Man,” in C. S. Lewis’s List: The Ten Books That Influenced Him Most, ed. David Werther and Susan Werther (New York: Bloomsbury, 2015), 31–48.

- See Donald T. Williams, “C. S. Lewis on Truth,” in Reflections from Plato’s Cave: Essays in Evangelical Philosophy (Lynchburg, VA: Lantern Hollow Press, 2012), 103–28.

- C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: MacMillan, 1943), 122.

- C. S. Lewis, The Collected Letters of C. S. Lewis, 3 vols., ed. Walter Hooper (San Francisco: HaperSanFrancisco, 2004), 3:393.

- C. S. Lewis, “Learning in Wartime,” sermon preached at St. Mary the Virgin, Oxford, October 22, 1939, in The Weight of Glory and Other Addresses, ed. Walter Hooper (San Francisco: Harper Collins, 1980), 58.

- C. S. Lewis, Out of the Silent Planet (New York: Simon and Schuster Inc., 1996), 154.

- “Christian Apologetics,” 93.

- Mere Christianity, 43.

- Collected Letters, 2:674.

- “Christian Apologetics,” 98–99.

- Francis Schaeffer, The God Who Is There: Speaking Historic Christianity into the Twentieth Century (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1958), 152; cf. The Mark of the Christian (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1970).

- C. S. Lewis, “Man or Rabbit?” in God in the Dock, 109.

- Collected Letters, 2:659.

- “Christian Apologetics,” 103.

- C. S. Lewis, Prince Caspian (New York: HarperCollins, 1979), 156.

- C. S. Lewis, The Last Battle (New York: HarperCollins, 1984), 185–86.

- Austin Farrer, “The Christian Apologist,” in Light on C. S. Lewis, ed. Jocelyn Gibb (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1965), 26.

- C. S. Lewis, “On Obstinacy in Belief,” in The World’s Last Night and other Essays (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1960), 25.

- Ibid., 26.

- C. S. Lewis, Till We Have Faces: A Myth Retold (New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World, 1956; repr., Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1968), 308.