This article first appeared in the Effective Evangelism column of the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 40, number 02 (2017). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For further information or to subscribe to the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, click here.

I’ve discovered that it is often useful to prepare people for the gospel by asking them some key philosophical questions. One reason I do this is to help people recognize that truth is exclusive. In our postmodern culture, people think that we all create our own truth, so why would it matter what religion we believe? Universities claim to teach young people to think, but most teach relativism and thus undermine even the most basic distinction between truth and falsehood. Therefore, I frequently help an unbeliever understand the concepts of truth, knowledge, and the law of noncontradiction. Sometimes I’ll begin a discussion by asking a person how he would answer the “three great philosophical questions of life,” which deal with origin, purpose, and destiny.

To be honest, starting with philosophical questions is a lot of fun, too. I enjoy helping people think through these issues, and this approach acts as a great launching pad into discussions about Christ and Christianity.

The Great Questions of Life. Recently, I walked into a frozen yogurt shop and ordered a bowl of delicious black raspberry Yagööt. While waiting for the order, I asked Tatyanna, the server, if she’d ever taken a philosophy course in college. She said she enrolled but then withdrew because she couldn’t understand it, though she was interested in the subject. I told her that I taught philosophy and wondered how she would answer the three great philosophical questions of life (Where did I come from? Why am I here? and Where am I going?). Tatyanna said, “Well, my science teacher said that we evolved, and I don’t know why I’m here.” So we talked a bit about evolution and the need for a First Cause before I picked up my yogurt and went my way.

What Is Truth? A couple days later, I took my daughters into the same store, and Tatyanna was there again. I smiled and said, “Tatyanna, I have another philosophical question for you.” She seemed glad to see me and asked what the new question was. I asked, “How would you define truth?”

She said, “Truth is what you believe.”

Glancing out the window, I responded with an illustration. “If I said that it was raining outside this store right now, would that be a true or false claim?” She said it would be false. “Why?” I asked.

She responded, “Because it is not actually raining out there right now.” I said, “Right; a claim is true only if it corresponds to reality. It must match the way things really are in order to be true. Truth is an idea or statement that corresponds to reality. Just believing something doesn’t make it true.” I continued, “If truth must correspond to reality to be true, then is truth something that we create or something we discover?”

She suggested, “Something we discover?”

“Yes,” I said. “Truth exists outside ourselves; it is objective. It is not something we make up, but something we find.” I encouraged her to become a seeker of the truth, since there are real and objective answers to life’s great philosophical questions, and it is in our best interest to discover those answers.

Before I left the store, she asked me if I could give the next questions to her ahead of time so she could be more prepared. She wrote them down.

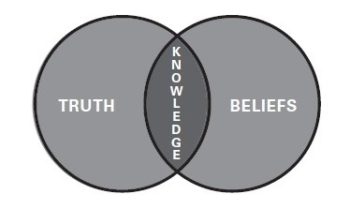

True Belief. When I came back a few days later, she was ready with an answer to my first question: What is knowledge? She said that knowledge is everything that we learn. Trying to help her focus her definition, I drew a diagram that looked like this:

I explained that there are some things we might believe that aren’t true. There are many things that are true that we don’t yet believe. There are many things that are true that we do believe. Knowledge is contained in the overlap between our beliefs and the truth. Knowledge is the truth that we believe, or true belief (technically, justified true belief). If we don’t believe the truth, it is not knowledge for us, since we don’t “know” it.

If we want the overlap between truth and belief to be greater, we need to discover more things that are true (that match reality). The most important truths to discover are those that relate to the great questions of life.

The Answer to the Big Questions. The second question I had Tatyanna write down earlier was “What is the basic message of the Bible?” The answer also can be the answer to the three “great questions.” Once Tatyanna shared her thoughts on the Bible, I summed it up by drawing out the illustration that shows how God created us [origin] to have a relationship with Him [purpose], but we broke that relationship by our sin. This caused a gulf between us and God, but Christ bridged the gap through His death and resurrection. If we turn from our sin and trust Him for salvation, we can participate in His Kingdom and go to heaven instead of hell [destiny].

Just this past weekend I had a follow-up conversation with Tatyanna. She remembered how to define truth properly (she said the rain illustration had helped a lot), and she gave a good answer about the purpose for our existence. We plan to talk more.

Socratic Method. At a mall, I had another engaging encounter with a guy I’ll call Scott, who was running a tablet repair kiosk. The conversation went something like this: I asked, “How’s business?” Scott said, “Slow. Real slow. This mall isn’t what it used to be.”

Since he wasn’t busy, I chatted with him for a while about his repair business, and then we talked about our respective college experiences. “One of my favorite courses to teach is philosophy,” I said.

“Really? Philosophy is deep.” He seemed intrigued, so I began to ask him some philosophical questions. How would you define truth? How would you define knowledge? After a few minutes talking about the nature of truth and knowledge, I asked him how he would answer the three great philosophical questions of life.

Scott quickly showed himself to be an agnostic who believed in naturalistic evolution. He struggled with the second and third questions and finally gave up. “How would you answer these questions?” he asked. Rather than going directly to the Bible, I decided to use the Socratic method to help him come to his own conclusions that would point him in the direction of Christianity.

Origins. I asked Scott, “Could something come from nothing?” He said, “No.”

Then I said, “If something cannot come from nothing, then if anything now exists, then something must have always existed. Right?” He agreed. I asked, “Do you agree with the vast majority of scientists who say that the universe had a beginning?”

He said, “Yes.”

“So if the universe had a beginning, and could not have come from nothing, then something existed beforehand that was responsible for bringing the universe into existence, right?”

“Yes.”

“What would this eternal ‘something’ need to be like to bring about the universe? Wouldn’t it have to be very powerful and intelligent?” Once he accepted that, I asked, “Wouldn’t you think that if this eternal, all-powerful being put us here, He would want to let us know why? Especially since we have the capacity to think about these questions, and we have the desire to know the answers.” This reasoning made sense to Scott, and I proceeded: “If He did reveal Himself to us, then how do you think He did?”

Law of Noncontradiction. We talked about different options out there, like the Qur’an or the Bible. I told him that there are many religions with revelation claims, but that they could not all be true. Why not? Because they contradict each other. According to the law of noncontradiction, something cannot both be true and not true at the same time and in the same sense. Religions often make opposite claims. For example, Christianity says that Jesus is God’s Son, whereas Islam says that God cannot have a son. But Jesus either is the Son of God, or He is not. If He is, then Islam could not be true. If He isn’t, then Christianity could not be true. There are fundamental differences in these religions. The various religions could logically all be false, but they could not all be true.

Proof for the Bible. I suggested to Scott that the proof for the resurrection of Jesus makes the Bible the best option as a revelation from God. I told him, “If Jesus actually rose from the dead, the ramifications of that are huge! It would mean that He is who He said He was (God the Son), that He is the only way to God, as He claimed to be, and that the Bible is God’s Word, as He said it was!”

At this point, Scott asked, “So, are you a Christian?” When I affirmed that, he then asked, “Well, doesn’t that make you biased?”

I said, “No, I think I can be more objective about deciding what religion is true because of the value I place on truth’s correspondence to reality. As an honest truth seeker, I’m a Christian because I have good reasons to be.”

In his case, it was helpful that I had earlier defended proper definitions of truth and knowledge. It was also probably good that I tried to help him discover the truth for himself instead of just telling him what I believe.

Scott and I talked for just a bit more after that. As I often do when I get to this part of the conversation, I encouraged him to investigate the evidence for the resurrection of Jesus. We parted on friendly terms, and I was once again reminded of the vast numbers of unbelievers who are open to an evangelistic approach of listening and engaging on a philosophical level. This easy-going approach using guiding questions can lead to many opportunities to share the good news of Jesus.

—Mark Bird

Mark Bird (DMin) teaches theology, evangelism, and philosophy at God’s Bible School and College (Cincinnati), where he also directs online studies. He is the author of Defending Your Faith (Answers in Genesis, 2006), a twelve-lesson series in apologetics.