This article first appeared in the CHRISTIAN RESEARCH JOURNAL, volume 36, number 03 (2013). Note: This is part of our ongoing Philosophers Series.

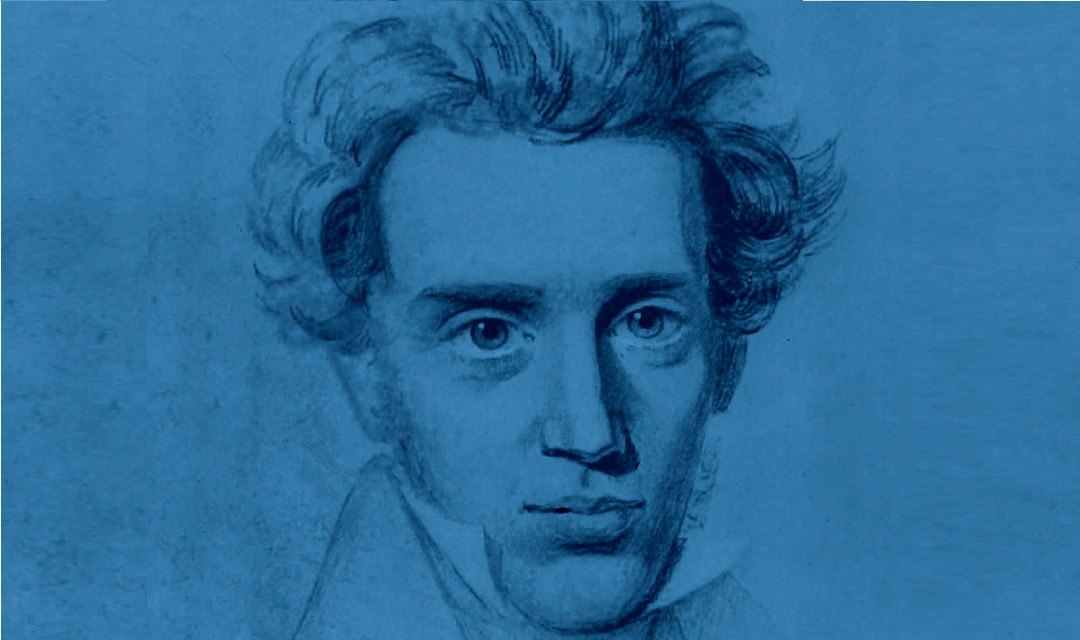

Søren Kierkegaard’s two heroes were Socrates and Jesus Christ. When explaining what he took his purpose as a philosopher to be, Kierkegaard said, “My task is a Socratic task—to rectify the concept of what it means to be a Christian.”1 This nineteenth-century Danish philosopher (1813–1855) is perhaps best known as the father of existentialism, a school of philosophical thought most often associated with atheist thinkers like Jean Paul Sartre. Kierkegaard, however, had a passionate faith in God. He was a staunch critic of the Danish church as well as a voice urging others to consider their need for God and His place in a truly fulfilled human existence. Much of what he wrote is strikingly relevant to contemporary life.

Kierkegaard is often misunderstood, in part because of the complexity of his approach as an author. Many of his works are written under particular pseudonyms. That is, Kierkegaard takes on a persona as an author and writes from a perspective different from his own. For example, in Fear and Trembling, a book that explores God’s testing of Abraham through His command that he sacrifice Isaac, Kierkegaard writes as Johannes de Silentio (“John of silence”). In the preface, John of silence states that he is not a philosopher.2 Instead, he is an outsider looking in at the faith of Abraham. He is trying to understand a faith that he does not have.3

Kierkegaard wanted to help people discover and ultimately live the truth for themselves, which may be one of his motivations for writing from the perspective of different characters. Because Kierkegaard employs pseudonyms in this way, he is often misinterpreted. To understand his views, it is best to look to the works published under Kierkegaard’s own name, such as his series of edifying discourses4 and Works of Love.5 We can learn of his views in the pseudonymous works as well, but careful interpretation is needed.

HIS LIFE

Kierkegaard is said to have inherited his propensities for guilt and melancholy from his father, Michael, who was a strictly religious man. Michael believed that all of his seven children would die by the age of 33, the age of Jesus at His crucifixion. The reason may have been that he cursed God as a young boy, or that he impregnated his second wife Anne, Søren’s mother, before they were married. Interestingly, only Søren and one of his older brothers lived past the age of 33.

In 1840 Kierkegaard became engaged to Regine Olson. His inheritance from his father, who died in 1838, was large enough that he would not need to work, but it was not enough to support a wife and children. Ultimately, Kierkegaard broke off the engagement, which he justified as necessary to fulfill his divine calling as a writer. It is clear that his relationship with Regine had a lasting impact on him, and its ending was felt by him to be a painful sacrifice.6 But he apparently believed that it was a sacrifice with a divine purpose.

EXISTENTIALISM

Existentialists have many differences, but there are some common concerns that guide their philosophical thinking.7 First, existentialists believe that freedom is the distinct trait of human beings. The existentialist wants to enable people to experience and practice their freedom as they choose what to value and how to live. Second, existentialists also seek to convert their readers. They want the reader to see that she has been deluded in some way, and to take a radically new perspective. This is similar to a religious conversion, and in fact for Kierkegaard it includes such a conversion. For other existentialists, the new perspective may not include God at all, but a purely human point of view. Existentialists argue that if we accept the fact of our freedom and the responsibility that goes along with it, we will be changed.

Another key component of existentialism is the belief that emotions can be a means of understanding.8 Existentialists believe that human beings can come to know things through certain moods or feelings. For example, if a person feels a sense of fidelity to a friend who has died, this points him to the existence of God, who is the source of fidelity. The emotions of despair and guilt have important roles in Kierkegaard’s philosophy and the human quest for meaning and satisfaction in life.

STAGES ON LIFE’S WAY

Kierkegaard believed that philosophy should focus on life’s deep questions related to God, humanity, ethics, and meaning. He approaches these issues not merely in an abstract sense, but in a way that is both practical and prophetic. In keeping with his belief that philosophy should be relevant to our daily lives and speak to our deepest concerns, Kierkegaard discusses a process by which human beings can acquire deep satisfaction and become authentic persons. In order to understand this process, he often discusses the stages on life’s way.9

Aesthetic Stage

The first stage on life’s way is the aesthetic stage. The main goal of a person in this stage is to satisfy her desires. These desires could be for many different things. The hedonist in pursuit of sensual pleasures is the perfect example of life in this stage. Because she is driven by her desires, she is not truly free and fails to have a consistent character. But a problem arises, even if she gets what she wants. Given their nature, humans are not satisfied with mere pleasures, whether from food, drink, sex, or television. We need something more; this type of life is empty. Because of this, a person living in this stage will at some point experience despair. This emotion of despair, then, is a means by which she can come to know that she must change, that life as she is living it is not now and cannot ever be truly satisfying. In response, she may seek out more or different pleasures in her quest for satisfaction, or she may move to the next stage on life’s way. If she does, she can make progress towards living out her freedom rather than being captive to her desires.

Ethical Stage

The second stage is the ethical stage, in which the primary goal is to live according to ethical truth. In this stage, there are moral limits on what one can and cannot do. The individual takes responsibility for herself and her choices, and seeks to become what she ought to be. She seeks to fulfill her duties related to her work and her relationships. The ethical life introduces sacrifice; the self is no longer at the center of everything as it was in the previous stage. However, a new problem arises that prevents her from being truly fulfilled. She reflects on her life and realizes that she does not always do what she ought to do. No one does. This leads to a new problem, the problem of guilt and the despair that it produces. These emotions show her that a further change is needed if she is to be fulfilled. In response to this, she may simply try harder to do the right thing, to be the kind of person she wants to be, or she may move to the third and final stage.

Religious Stage

The religious stage is where the individual finds true fulfillment, and becomes truly authentic. Here, one realizes that she cannot always do the right thing. This is a fact of human nature that she accepts. She also receives forgiveness from God, which resolves her guilt and eradicates her despair. She is now becoming an authentic individual because she is rightly related to God by a passionate faith in Him. She has been converted; she sees her life from a new perspective. For Kierkegaard, the religious person is no sour ascetic. Instead, she realizes the goodness of creation, and takes the sensual pleasures of food, drink, and sex to be gifts from God to be enjoyed in the right way. By grace she is rightly related to the physical world, other people, and God. Her physical and spiritual aspects are integrated in a way that brings wholeness and integrity to her character and to her life. For Kierkegaard, this is what it means to be a Christian.

Institutional Christianity, or “Christendom,” as he often referred to it, was beset by hypocrisy and consisted of empty ritual. By contrast, an authentic Christianity is a personal, passionate, inner faith that leads one to act in the world.

FAITH, REASON, AND THE ABSURD

Kierkegaard is commonly thought to hold the view that faith and reason are opposed to one another. Many readers of his works come away thinking that for him faith is irrational. This confusion is sometimes due to the way Kierkegaard uses the terms “objectivity,” “subjectivity,” and “absurd.”

Kierkegaard seems to be critical of objective truth and a believer in the subjectivity of truth. But he is no relativist. In fact, his aim is to preserve objectivity but to keep it deeply connected with a passionate subjectivity, or a deeply held inward commitment that moves one to obey God through acting in the world.10 He believes that one ought to give careful thought to one’s goals and perspective on the world. He believes that there are objectively true moral principles, and that humans have moral obligations connected to the various roles they inhabit (such as parent, ruler, or employee). He also believes that there is an objective reality that can be known and engaged, including divine reality.

What Kierkegaard is critical of, and rejects, is the form of objectivity that undermines a person’s self-understanding as an individual responsible for his actions, convictions, and concern for truth. For example, he would reject the notion that we are merely complex biological machines at the mercy of the laws of nature, because this view undermines individual responsibility. He would also be critical of the person who claims to know the truths of Christianity, but does not live them. These truths must be grasped subjectively and lived out in daily life, if they are to be truly known.

Another reason that Kierkegaard is thought to believe that faith is irrational has to do with the concept of the absurd in his writings. Many interpret Kierkegaard as holding the view that individuals should take a blind leap of faith and believe in something that is contradictory. Contemporary Christian philosopher Robert Adams thinks this interpretation is misguided, however, based on his reading of Fear and Trembling.11 When a person of faith embraces the absurd, it is not that he believes something that is contradictory. Rather, the absurd refers to a believer giving up his claim but not his care for someone or something that he loves.

Abraham illustrates this when he binds Isaac and is prepared to offer him to God as a sacrifice. Abraham loves Isaac with all that he is. He gives up any claim to Isaac as he intends to offer him as a sacrifice, but never renounces his love for Isaac. By faith he receives Isaac back again as the angel of the Lord tells him to relent. To receive back that which one has given up is the movement of faith. This same faith is important for others as well. Humans are to renounce their claim on the finite goods of the world, but in the same moment receive them back from God by faith. It is this concurrent resignation and reception that is the absurd, for Kierkegaard. But it is also the right thing to do.

RELEVANCE FOR TODAY

First, a central truth in the works of Søren Kierkegaard is that we must obey God, even when this looks preposterous to others. Abraham, Noah, and the apostles are biblical examples of such obedience. Authentic faith is different from dead religion because it produces genuine obedience and love of both God and others.

Second, Christians are to renounce the world but then receive it back from God by faith to be enjoyed and experienced in the ways He intends. Believers are to renounce their claim on, but not their care for, what and whom they love. We can enjoy the finite goods of earthly life, but we must depend on God for our ultimate happiness.

Finally, if Kierkegaard were alive today, he would exhort people to take responsibility for themselves and their choices. He would have little patience for shifting responsibility to genetics, environment, or upbringing. For Kierkegaard, a living faith is one that expresses itself in works of love for God and others (see Gal. 5:16). Ultimately, each person is responsible for who they are and how they live, and can only achieve their full potential through a passionate and living faith in God. This is what it means to truly know God in Christ.12

Michael W. Austin is professor of philosophy at Eastern Kentucky University, where he specializes in ethics. His most recent book is Being Good: Christian Virtues for Everyday Life (Eerdmans, 2012).

NOTES

- Søren Kierkegaard, Attack upon Christendom, in Existentialism, 2nd ed., ed. Robert Solomon (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 23.

- Søren Kierkegaard, Fear and Trembling (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 3– 6.

- Stephen Evans, Kierkegaard on Faith and the Self (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2006), 213.

- Søren Kierkegaard, Eighteen Upbuilding Discourses, trans. Howard and Edna Hong (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1992).

- Søren Kierkegaard, Works of Love, trans. Howard and Edna Hong (London: Collins, 1962).

- William McDonald, “Søren Kierkegaard,” The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2005; http://www.iep.utm.edu/kierkega/ (May 10, 2012).

- Mary Warnock, Existentialism (New York: Oxford University Press, 1970), 1–22. For a criticism of reading Kierkegaard as a particular kind of existentialist, and a general introduction to his thought, see C. Stephen Evans, Kierkegaard: An Introduction (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009).

- David E. Cooper, Existentialism: A Reconstruction, 2nd ed. (Malden, MA: Blackwell, 1999), 17–18.

- Kelly James Clark and Anne Poortenga, The Story of Ethics (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2003), 91–95. See also the following works by Kierkegaard (various editions): Stages on Life’s Way, Either/Or, The Sickness unto Death, and his Journals.

- Edward Mooney, Knights of Faith and Resignation (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 1991), 74–77.

- Robert Adams, “The Knight of Faith,” in The Existentialists, ed. Charles Guignon (Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 2003), 19–31.

- I would like to thank Adam Pelser for his excellent comments on an earlier version of this article.