This article first appeared in the Practical Hermeneutics column of the Christian Research Journal, volume 31, number 03 (2008). The full text of this article in PDF format can be obtained by clicking here. For more information about the Christian Research Journal, click here.

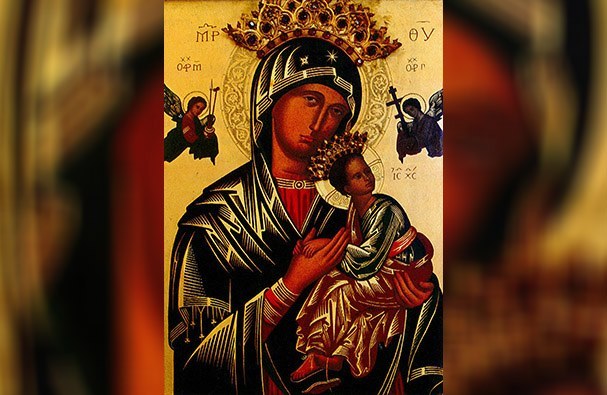

Roman Catholic theology often parallels Mary the mother of Jesus with Jesus Himself in His work of redemption. For example, Jesus is born without the stain of original sin, and so is Mary. Jesus lives a sinless life; so does Mary. Jesus remains a virgin all His life; Mary is Ever-Virgin. Jesus is the Redeemer; Mary is Co-Redemptress. Jesus is the one Mediator between man and God, yet Mary, too, is Mediatrix. Jesus is bodily assumed into heaven; so is Mary. Ascribing Christological attributes such as these to Mary historically has been a source of contention between Protestants (who see no basis in Scripture for these beliefs), and Roman Catholics (who emphasize the role of “Tradition” in these matters).

Defining Terms. All of these beliefs, save two, are official Roman Catholic dogmas. The exceptions—Co-Redemptress and Mediatrix—are nevertheless hallmarks of Roman Catholic devoutness that many believe to be ripe for dogmatic definition.

These two titles, often considered as a single role for Mary, are technically distinct. Redemptress broadly involves Mary’s active decision to bring redemption to the world by agreeing to become the mother of Jesus, whereas Mediatrix has to do with Mary’s active work in continually advocating for the salvation of those who take refuge in her. The Roman Catholic teaching for both is summed up well in the document Ineffabilis Deus: “All our hope do we repose in the most Blessed Virgin—in the all fair and immaculate one who has crushed the poisonous head of the most cruel serpent and brought salvation to the world [hence, Redemptress];… in her who, with her only-begotten Son, is the most powerful Mediatrix and Conciliatrix in the whole world;…in her do we hope who has delivered us from so many threatening dangers.”1

Despite efforts by some Roman Catholic scholars to downplay statements such as these and to mitigate the excesses that plague these roles for Mary, traditional Roman Catholic piousness still rules in defining what Catholics believe about these issues; namely, that Mary plays a part in objective redemption, in her role as Redemptress (in that apart from her consent to bear the Son of God, the entire world would be forever lost) and in her role as Mediatrix (in that she actively dispenses salvific graces to the faithful and intercedes to her Son on their behalf in such a way that Christ cannot resist her intercession).

Eadmer (A.D. 1060–1124), an English monk and student of Anselm, illustrates well the excesses of this view: “Sometimes salvation is quicker if we remember Mary’s name than if we invoke the name of the Lord Jesus.” Roman Catholic apologists express these sentiments in a different way today, but that should not be misconstrued as constituting a disagreement with these statements of Marian piety. When confronted with these statements about Mary, Roman Catholic apologists are quick to attempt to justify them even from Scripture itself.

The Alleged Scriptural Basis for a Redemptress. The main proof text for viewing Mary as a Redemptress is found in the first chapter of Luke’s gospel. This single chapter acts as the primary scriptural basis for Mary’s supposed immaculate conception (“Hail, full of grace,” v.28, Douay-Rheims), her special status among believers (“The Lord is with you,” v.28), her perpetual virginity (“How will this be since I am a virgin?” v.34), her status as “mother of God” (“Why is this granted to me that the mother of my Lord should come to me?” v.43), her unique “blessedness” (“Blessed are you among women,” v.42, and “All generations will call me blessed,” v.48), as well as her role as Redemptress. A full examination of this chapter as a support for these beliefs is not possible in this brief article; I refer you elsewhere for a fuller treatment. We will instead focus on the single verse in this chapter that is alleged specifically to support Mary’s role as Redemptress.

In Luke1:38, after the angel announces to Mary that she by the power of the Holy Spirit would conceive a child who would be called the Son of God, Mary responds simply, “Behold, I am the servant of the Lord; let it be to me according to your word.” Roman Catholic scholar John McHugh sees in Mary’s statement a fiat (i.e., a consent to participate in the divine plan) rather than simply a humble submission to God’s will. Catholic theologian Tina Beattie goes so far as to insist, “There was no implicit threat in God’s invitation, and no fear of punishment. If she chose the quiet life, she would be left at peace. The decision was hers and hers alone.… The history of the world hung in the balance as a young girl considered the options before her.”

Catholic New Testament scholar Francis Moloney contends that “Mary must be seen as free to respond or not to respond to this initiative of God.” Catholic author Neal Flanagan, in his Marian Creed, writes, “I believe that Mary’s Fiat initiated the Christian era….and inserted her intimately into Christ’s salvific work.” The tacit assumption of Moloney (and the not so tacit assumption of Flanagan and others who make this point) is that the redemption of the world is contingent upon Mary’s decision to accept God’s course for her life.

A Biblical Response. These examples are all instances of pressing Scripture far beyond the intent of the writer to engage in special pleading in the case of Mary. Special pleading is a form of logical fallacy that applies when someone argues for an exemption of his case from a generally accepted rule or principle without justification for that exemption. Other biblical characters may be found in circumstances similar to Mary’s, and thus we should apply the same hermeneutic we apply in those cases to the case of Mary. The Catholic writers mentioned in the previous section fail to do so, however, and instead interpret Luke1:38 with a special significance. If we apply their hermeneutic to Mary’s choice to accept God’s plan for her to bear His Son, and thus label her Co-Redemptress, then we must apply this same hermeneutic to Paul’s decision to accept God’s charge for him to take the gospel to the Gentiles. Are we to conclude that, had Paul refused, God would have counted His losses and worked only with the Jews? Mary’s “decision to cooperate” is irrelevant in God’s salvific plan. God simply announces that Mary will bear His Son; He does not ask her permission.

Mary’s cooperation can be no more significant here than Joseph’s cooperation in Matthew’s account, according to which it is Joseph who must make the decision to take Mary as his wife. If Joseph had refused, Mary (as an unwed, pregnant woman) would have been accused of adultery and ostracized—perhaps even stoned, which would have killed both mother and child! None of the exegetes who see special significance in Mary’s “fiat” in Luke1, however, go so far as to speak of Joseph’s “fiat” in Matthew1, or to conclude that Joseph is somehow a “Co-Redeemer” because of his decision to stay with Mary.

There is, further, no basis for viewing Mary’s cooperation in God’s plan of salvation as any more significant than that of, say, Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Gideon, or Jeremiah. Each of them was equally instrumental in effecting that same plan throughout salvation history.

What, moreover, are we to make of those examples where God’s purpose is accomplished in spite of—or perhaps even because of—an agent’s disobedience? Tamar, by posing as a prostitute, conceived an illegitimate son who was in the direct lineage to the Messiah (Gen.38; cf. Matt.1:3). God put to death two of Judah’s sons because of their disobedience, and Judah himself unwittingly became the father of Tamar’s children through his own sinful relationship with her. Pharaoh, similarly, attempted to thwart God’s purpose by refusing to comply with His plan to free Israel; yet Paul could cite this episode as an integral part of God’s plan: “For the Scripture says to Pharaoh: ‘I raised you up for this very purpose, that I might display my power in you and that my name might be proclaimed in all the earth’” (Rom.9:17).

I could add multiple examples without difficulty, including that of Jonah, who complied with God’s plan only with great reluctance—and even of Judas, whose betrayal of Jesus is seen by the New Testament writers as entirely necessary in redemption: “The Son of Man will go as it has been decreed, but woe to that man who betrays him” (Luke22:22; cf. Matt.26:23 and Mark14:20). Far from endangering the preservation of God’s people through their unwillingness to cooperate with God’s plan, these individuals either were chastised until they did cooperate, replaced by others who would cooperate, or compelled to cooperate unwittingly as agents of the very plan they opposed! The suggestion that God requires Mary’s cooperation to bring about redemption for His people is little more than a gratuitous (and quite unbiblical) assumption.

Catholic theologian Richard Sklba’s comment on Mary’s response in Luke1:38 seems on the whole much more reasoned: “She took her place among [those] who had no recourse except to respond, ‘be it done to me according to your word’ (Lk1:38)….She awaits the command of another. The last word on the subject is not really her own.” Certainly, this is the intent of Mary’s response; not the theologically bloated fiat “exegesis” offered by Rome. Mary, as a “bond servant [slave] of the Lord,” does not presume to hold God, His salvation, and the rest of the world at bay while she ponders a decision; rather, she humbly submits to the plan of God because it is the only response that is fitting for a servant of the Lord.

— Eric D. Svendsen

NOTES

- Pope Pius IX, Mary Immaculate: The Bull Ineffabilis Deus (Paterson, NJ: St. Anthony Guild Press, 1946), 23.

- Eadmer of Canterbury, Liber de Excellentia Beatae Mariae in Jacques-Paul Migne, Patrologia Latina, Vol 159 (Paris: J. P. Migne, 1844–1855), 309, quoted in J. Shinners, “The Cult of Mary and Popular Belief,” in Mary, Woman of Nazareth: Biblical and Theological Perspectives, ed. Doris Donnelly (New York: Paulist, 1989), 170.

- Unless otherwise noted, all Bible quotations are from the English Standard Version.

- For an exhaustive treatment, see Eric D. Svendsen, Who Is My Mother? The Role and Status of the Mother of Jesus in the New Testament and Roman Catholicism (Amityville, NY: Calvary Press, 2001).

- John McHugh, The Mother of Jesus in the New Testament (Garden City, NJ: Doubleday, 1975), 65. Cf. William G. Most, “Unscriptural Marian Doctrine?” Homiletic and Pastoral Review 94 (May 1994): 61.

- Tina Beattie, Rediscovering Mary: Insights from the Gospels (Liguori, MO: Triumph Books, 1995), 23.

- Francis J. Moloney, Mary: Woman and Mother (Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1988), 19.

- See Neal Flanagan, “Mary of Nazareth: Woman for all Seasons,” Marianum 48 (1986):167.

- Richard Sklba, “Mary and the ’Anawim,” in Mary, Woman of Nazareth: Biblical and Theological Perspectives, ed. Doris Donnelly (New York: Paulist, 1989), 124–26.