This is an online article from the Christian Research Journal.

When you support the Journal, you join the team and help provide the resources at equip.org that minister to people worldwide. These resources include our ever-growing database of more than 2,000 articles, as well as our free Postmodern Realities podcast.

Another way you can support our online articles is by leaving us a tip. A tip is just a small amount, like $3, $5, or $10, which is the cost of a latte, lunch out, or coffee drink. To leave a tip, click here

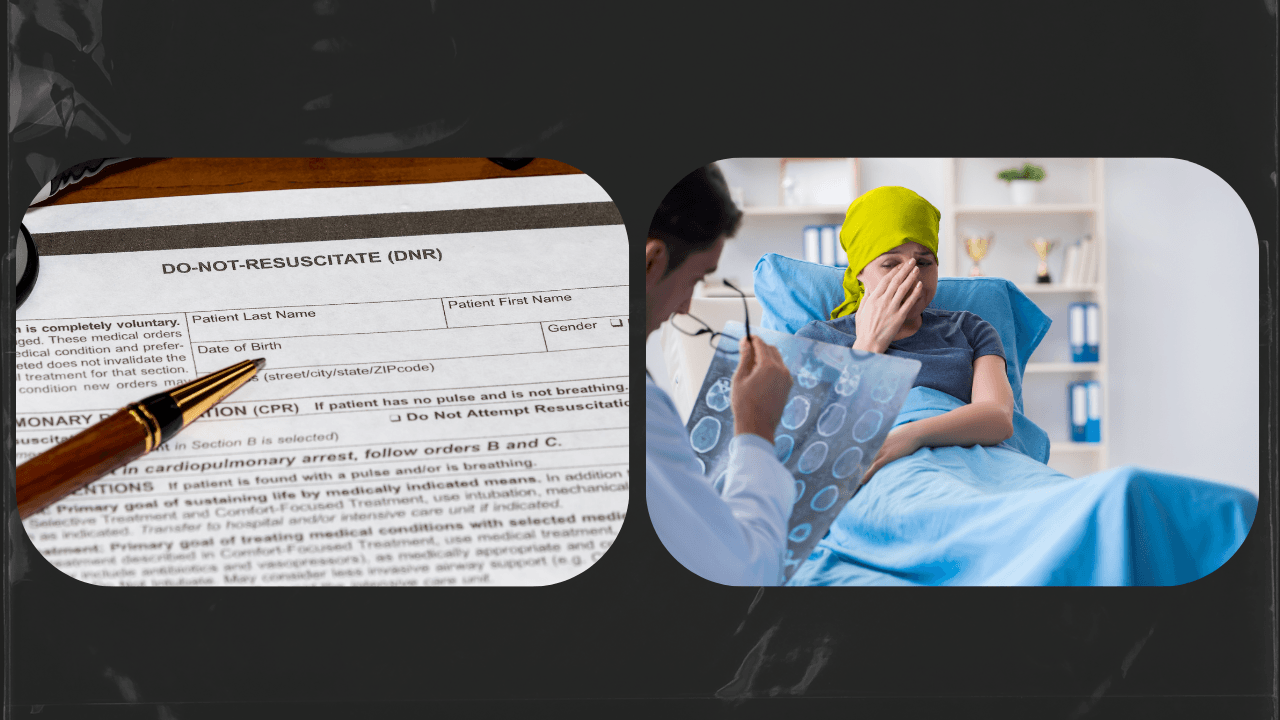

The patient was an emaciated eighty-eight-year-old man whose late-stage cancer had spread to his bones and his brain. When his breathing stopped, a code was called, and a team of medical personnel — doctors, nurses, techs, social workers, and chaplains — rushed to his room. Performing their choreographed tasks, they restored his breathing. But in order to do so, they had to insert a breathing tube into his airway, and he had to be placed on a ventilator and moved to the ICU. The team knew it was only a matter of time before his heart stopped again. He was dying. Dr. L. S. Dugdale, the attending physician and author of The Lost Art of Dying, asked the daughter if she would like to have a Do Not Resuscitate order in place so he wouldn’t have to endure the physical trauma of being resuscitated again. The daughter adamantly refused, saying that she was a Christian, and that she believed God would work a miracle. As Dr. Dugdale says, “It seems curious that the people who believe most fervently in divine healing cling most doggedly to the technology of mortals.”1

Medicalized Dying

No doubt, many of us are alive today because of post-World-War-II medical advances, such as antibiotics, surgery, and chemotherapy. We are grateful for modern medicine. Yet modern medical advances have led to something doctors and theologians alike refer to as “medicalized dying.” “In medicalized dying, death is regarded as the great enemy to be defeated by the greater powers of science and medicine.”2A variety of life-sustaining measures exist, such as CPR, dialysis, ventilators, artificial nutrition, and more. In order to glorify God in our bodies (see 1 Corinthians 6:20), we do want to seek and accept medical care that is likely to “maintain or restore our health” by “ordinary means.”3 At the same time, we recognize that “God’s Word…[makes] it permissible in some cases to decline or discontinue life-sustaining treatment” at the end of life.4

Studies show that Christians are more likely to choose aggressive medical measures at the end of life than non-Christians.5 When we take the time in advance of crisis to educate ourselves about such measures and to understand the biblical principles that guide us, we will be better prepared to make wise and loving decisions in difficult moments. As we consider prayerfully what it looks like to glorify God at the end of life and what quality of spiritual life we want to enjoy, we can make advance directives that guide our loved ones about our wishes and bring them peace in painful moments. We can also help loved ones in case of our incapacitation or death by organizing documents and information, such as wills, durable power of attorney, and passwords.

Aggressive Measures at the End-of-Life: What We Need to Know

Many of us learned about end-of-life measures by watching medical dramas in the media. Sadly, TV and movies rarely depict these aggressive medical measures accurately. Let’s consider TV CPR.6 On TV, a bedside monitor shows that the heart has stopped, a code is called, people rush in, someone yells “clear!” the heart is shocked, and the rhythm returns. By the end of the episode the patient is well and leaves the hospital. In reality, ribs are often fractured, blood is often spilled, the patient is always placed on a ventilator and moved to ICU, and fewer than ten percent of patients recover to leave the hospital after CPR.7 This does not mean that we should never allow CPR; it does mean that a person near the end of life and/or with a terminal illness should pray about whether or not to have a Do Not Resuscitate order disallowing CPR.

In the same way, mechanical ventilators, which “support breathing in the setting of respiratory failure,”8 dialysis, which “replaces kidney function, most commonly by filtering blood through a machine,”9 artificially administered nutrition, which is delivered “through tubes entering our gastrointestinal tract” or “via catheters placed in large veins,”10 among other medical measures, are complex and need to be considered carefully at the end of life. While they may have much to offer a relatively healthy patient to restore health, they may act only to prolong death in a dying person. For this reason, we need to approach these measures prayerfully, armed with biblical principles. As Dr. Kathryn Butler explains, “Our path requires careful review of the factors influencing survival and reflection upon Scripture to do as God requires: ‘to do justice, and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God’ (Mic. 6:8). In short, we need to determine when to press on and when to relax into the embrace of our Lord.”11

Biblical Principles Concerning End-of-Life Measures

After educating ourselves about end-of-life measures, we can use biblical principles to guide us as we consider the options. In her book, Between Life and Death: A Gospel-Centered Guide to End-of-Life Medical Care, Dr. Butler recommends considering four biblical principles:

- Sanctity of life

The Lord who created male and female in His image (Genesis 1:26), who “gives to all mankind life and breath and everything” (Acts 17:25), has written dignity into the very being and body of every human.

- God’s authority over life and death

God rules over the life and death of something as ordinary as a sparrow (Matthew 10:29), and God rules over the life and death of His creation. When considering which measures to accept or refuse at the end of life, we must remember, “Sanctity of life does not refute the certainty of death.”12

- Mercy and compassion

We should be guided by compassion for the person at the end of life and should seek to bring comfort without inflicting further suffering. A compassionate approach considers a person’s wishes for the ability to connect with God and with others.

- Hope in Christ

Because Christ has defeated death, and because we have the hope of resurrection (see 1 Corinthians 15:52–55), we need not fear death but can anticipate the day of our homecoming.

Quality of Life Considerations

Armed with sound biblical principles, we can also consider the implications of choices we make at the end of life.

Hospital or Home. Many aggressive end-of-life measures require being in the hospital, often in the intensive care unit (ICU), where limitations are placed on visits from family and friends. For this reason, patients are often isolated in their final days and moments. A 2017 Kaiser Family Foundation study showed that 71 percent of Americans would prefer to die at home.13 If remaining at home with family and friends is our desire for the end of life, we need to know which measures would allow us to do so.

Financial Considerations. Although many Americans struggle to accept this reality, the cost of some treatments can be prohibitive. Dr. Davis makes excellent points about our responsibility to pay for treatments we choose and to consider stewardship of our finances, particularly as it concerns end-of-life measures. Consider, for example, a woman who had already been through rounds of chemotherapy to survive breast cancer. Years later, when she was diagnosed with late-stage pancreatic cancer, the doctors gave her little hope for survival. They recommended a costly experimental chemotherapy, saying it might add two months to her life expectancy of five months. The woman didn’t wish to spend her remaining time suffering the effects of chemotherapy, and she didn’t want to spend her children’s inheritance on something that gave her so little extra time. Yet many Christians were advising her that she must try the chemotherapy. Dr. Davis encouraged her with this biblical principle: “God’s Word requires us to make faithful use of all our talents, opportunities, and resources: time, energy, attention, and money.”14 For this reason, and because “earthly life is not the highest good,”15 Davis suggested that this woman could reasonably decline the costly chemotherapy.

Spiritual Quality of Life. It is not only okay, but it is good to consider our desires for a spiritual quality of life at the end of life. As we prepare our advance directives, we will want to ask questions like, “Will this option allow me to take in the ordinary means of grace — prayer, fellowship, communion, meditating on God’s Word?” In considering end-of-life stewardship of our bodies and our resources, we should ask not only, “What do I want?” but also “How will this option allow me to receive God’s love and continue to glorify God?” In making spiritual quality of life a goal for the end of life, we will demonstrate to others that whether we live or we die, our chief end is to enjoy and glorify God.

Gathering Essential Information

Armed with a biblical understanding of medicalized dying and the principles involved in making decisions about advance directives, we can gather important documents and information that will help our loved ones in case of our incapacitation and/or death. There are six essential steps in organizing such documents.

- Prepare an advance directive. An advance directive helps to guide medical care decisions in the case of incapacitation. It allows us to appoint a health care proxy or surrogate and to indicate what kind of treatment we would choose or decline in medical crisis. As Dr. Davis explains, “Legally executed advance directives diminish the burdens of fear and indecision from all those who will have to make medical decisions for us if we cannot make them for ourselves.”16

- Appoint a durable power of attorney. A durable power of attorney has the legal power to act on our behalf if we are incapacitated. A power of attorney is granted the power to pay bills and execute financial actions. Some people appoint the same person as health care proxy and durable power of attorney, while others appoint different people.

- Create a will and appoint an executor. Even if we have very little property, it is crucial to make a will and to appoint an executor to handle our affairs after our death. Making a will is a way to steward the resources God has given us. It also clarifies wishes to loved ones about desires for property distribution.

- Organize and share passwords. Because phones and other technological devices hold valuable confidential information, it’s essential to secure them with a password and to share that password with one trusted person. Additionally, we need to gather our digital passwords in one secure location and to share that location with several trusted people.

- Gather other essential information. To help in the case of incapacitation or to wrap up affairs after death, we need to gather details about medical history, personal history, insurance information, titles and deeds, credit cards, bills, and methods of payment, and so forth. When my mother died, she left a filing cabinet full of essential information, with a folder called “Emergency” that had a cover sheet entitled, “What to Do When I Die.” In my shock and grief at her unexpected death, her guidance was a treasured gift.

- Provide information about wishes for body disposition and end-of-life services. When we die, our loved ones will be asked almost immediately about plans for disposition of the body. Making this decision now and communicating our wishes to our loved ones will save them much heartache in a time of shock and grief. Additionally, providing and when possible, paying for, funeral arrangements and end-of-life services in advance also eases the way for loved ones after our death.

Leaving a practical legacy such as this is no easy task. We can do the hard work of making such decisions in advance and gathering the crucial documents only by engaging in the ancient art of “remembering death.” Puritan Jonathan Edwards wrote, “Resolved, to think much on all occasions of my own dying, and of the common circumstances which attend death.”17

For a brief moment, let’s imagine the proverbial hit-by-a-bus scenario. We’ll do this together to make it less frightening. We are crossing the street, we are hit by a bus, and we are killed instantly. Immediately we find ourselves in the arms of our loving Savior, whose face smiles upon us. We know peace like we’ve never known. We are consumed by God’s glory.

Our families, on the other hand, are shocked and grieved to hear this news. But because we have talked many times with them about what to do if we are incapacitated (in case the bus actually left us in a coma) or dead, they know to head to the filing cabinet or to pull the binder out of the safe. When the police call to ask what is to be done with our bodies, they tell them the name of the funeral home in charge of arrangements. When it is time to read the will, the executor knows where to find it and why things are distributed as they are because we have explained our wishes. Our pastors know we want the gospel preached at our funeral. In the coming days, months, and years, they will continue to grieve, but they will have peace as they find the help we have left them. Why would we not offer such peace to the ones we love?

Elizabeth Reynolds Turnage (MEd, MACS) is an author, Bible teacher, and life and legacy coach. She has written two devotionals for people in crisis and is the author of Preparing for Glory: Biblical Answers to 40 Questions on Living and Dying in Hope of Heaven (P&R, 2024).

NOTES

- L. S. Dugdale, The Lost Art of Dying (New York: HarperCollins, 2020), 11.

- Alan Verhey, The Christian Art of Dying: Learning from Jesus (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2011), loc. 103, Kindle Edition.

- Bill Davis, Departing in Peace: Biblical Decision-Making at the End of Life (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R, 2017), 37; Davis cites the 1988 PCA Report on Heroic Measures (§ III.2–5).

- Davis, Departing in Peace, 37. Editor’s Note: For helpful discussion concerning the distinction between morally permissible (passive) euthanasia and morally impermissible (active) euthanasia, see the following articles: Hank Hanegraaff, “Is Euthanasia Ever Permissible?,” Christian Research Institute, March 19, 2024, https://www.equip.org/bible_answers/is-euthanasia-ever-permissible/; J. P. Moreland, “The Euthanasia Debate, Part One: Understanding the Issues,” Christian Research Journal, Winter (1992), https://www.equip.org/articles/the-euthanasia-debate-part-one-understanding-the-issues/; J. P. Moreland, “The Euthanasia Debate, Part Two: Assessing the Options,” Christian Research Journal 14, Spring (1992), https://www.equip.org/articles/the-euthanasia-debate-part-two-assessing-the-options/; Jay Watts, “Death with Dignity and the Imago Dei,” Christian Research Journal 38, no. 06 (2015), https://www.equip.org/articles/death-dignity-imago-dei/.

- See Andrea C. Phelps et al., “Religious Coping and Use of Intensive Life-Prolonging Care Near Death in Patients with Advanced Cancer,” JAMA 301, no. 11 (March 18, 2009): 1140–47, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.341.

- CPR stands for cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

- Kathryn Butler, Between Life and Death: A Gospel-Centered Guide to End-of-Life Medical Care (Wheaton: Crossway, 2019), 50.

- Butler, Between Life and Death, 80.

- Butler, Between Life and Death, 111.

- Butler, Between Life and Death, 98.

- Butler, Between Life and Death, 55.

- Butler, Between Life and Death, 35.

- Liz Hamel, Bryan Wu, and Mollyann Brodie, “View and Experiences with End-of-Life Medical Care in the US,” Kaiser Family Foundation, April 27, 2017, https://www.kff.org/report-section/views-and-experiences-with-end-of-life-medical-care-in-the-us-findings/.

- Davis, Departing in Peace, 26.

- Davis, Departing in Peace, 39.

- Davis, Departing in Peace, 32.

- Jonathan Edwards, Jonathan Edwards’ Resolutions: And Advice to Young Converts (n.c.: Ravenio Books, 2015), Kindle Edition.