This article first appeared in the Christian Research Journal, volume 27, number 1 (2004). For more information about the Christian Research Journal, click here.

SYNOPSIS

Everyone who has seen The Matrix trilogy knows that it presents a religious/philosophical worldview; what that worldview is, however, is a matter of debate. Some have argued it is Christian; some, Platonic (the philosophy of Plato); others, Gnostic (a Christian heresy); and still others, Buddhist. The films seem to use a combination of all of the above as metaphors for a postmodern worldview that deconstructs universal “savior” mythology into a Nietzschean “superman” philosophy in which one creates one’s own truth in a universe without God. In Nietzsche’s philosophy, our perceptions of reality are illusory (the theme in The Matrix) because they are part of the mechanistic determinism of nature (the theme in The Matrix: Reloaded). We must, therefore, create our own “new truth” through our human choices and beliefs (the theme in The Matrix: Revolutions). This worldview, however, is diametrically opposed to Christianity; hence, any similarities between themes or characters in The Matrix trilogy and orthodox Christianity are merely superficial.

“To be truthful means using the customary metaphor — in moral terms: the obligation to lie according to a fixed convention, to lie herd-like in a style obligatory for all.”1

— Friedrich Nietzsche

Mythologist Joseph Campbell sought to bring to light what he called the “monomyth,” the universal heroic journey common to all religions, which resides in the collective unconscious of humanity. The similarity of so many ideas and images in different religions is because they are ultimately diverse symbolic projections of the same physical and mental processes that are within all of us. In his interview with Bill Moyers in The Power of Myth, Campbell stated, “All the gods, all the heavens, all the worlds, are within us. They are magnified dreams, and dreams are manifestations in image form of the energies of the body in conflict with each other.”2

Campbell was a demythologizer. He deconstructed religious traditions and transcendent beliefs into their presumed origins in natural causes. Postmodern religion, like Campbell’s eclecticism, is a synthesis of diverse sources without regard for rational or organic consistency. It focuses on the parallels between religions while ignoring the disparities; it forces square similarities into round differences. I suggest this is also what the Wachowski brothers, Larry and Andy, have done with their cinematic Matrix trilogy. They have tapped into the ideas and images of diverse religious and philosophical views and used them as metaphors for a postmodern Nietzschean worldview of relativism, nihilism, and self-actualization.3

POSTMODERNISM AND REALITY

The genre of science fiction seems well suited for the postmodern suspicion of reality. Steven Connor writes in Postmodernist Culture, “Science fiction is a particularly intriguing case for postmodernist theory, precisely because the genre belongs, chronologically at least, to the period of modernism’s emergence. Modernism experimented with ways of seeing and saying the real; science fiction experimented with forms of reality themselves.”4

The Matrix has reshaped the sci-fi genre for our postmodern era. Its hero, Neo, keeps a secret computer disk hidden between the pages of a chapter titled “On Nihilism” in an actual postmodern book, Simulacra and Simulation, by Jean Baudrillard. The word simulacrum is defined by David Harvey as “a state of such near perfect replication that the difference between the original and the copy becomes almost impossible to spot.”5 This gives rise to the popular postmodern epistemological debate over the nature of knowledge and reality: How do we know that our understanding of reality is accurate? How do we know that we are not deceived in our perceptions? How can we ever escape our inherent subjectivity? In The Matrix, Morpheus echoes the essence of this postmodern questioning when he asks the as-yet-unenlightened Neo, “Have you ever had a dream, Neo, that you were so sure was real? What if you were unable to wake from that dream? How would you know the difference between the dream world and the real world?”

Neo soon discovers that what we all think is the real world is actually an illusion, a virtual reality created by artificial intelligence that has conquered the human race and turned it into an energy source for machines. Morpheus explains to Neo that the Matrix is a ruse to keep us from realizing that we are all blind and are born slaves.

CHRIST MYTHOLOGY

This “blind slavery” imagery is a fitting metaphor for humankind’s bondage to sin as described in the Bible. Jesus said that “every one who commits sin is the slave of sin” (John 8:34) and needs to be born again in order to see the kingdom of God (John 3:3).6 Being born again is not unlike Neo’s experience of waking up in his “pod” of slavery and being freed. The apostle Paul wrote that “the god of this world has blinded the minds of the unbelieving, that they might not see the light of the gospel” (2 Cor. 4:4).

The Christ symbolism woven into the story also is obvious. Morpheus, like John the Baptist, heralds the prophesied coming of “the One” (Neo), who will free people from their bondage to the Matrix. Neo is sought by the satanic gatekeeper (Agent Smith), is betrayed by a Judas (Cypher), is killed, is resurrected by the breath (a kiss) of Trinity, and ascends into the clouds as he heralds his and his followers’ intention to preach their “gospel” to all creation. In the first sequence of the first film, Neo delivers an illegal computer disk to a fellow hacker, who jokingly says of Neo, “Hallelujah. You’re my savior. My own personal Jesus Christ.” When people are freed from the Matrix, they go to a city called Zion — the same name as the biblical city of the Promised Land, which is symbolic of the redeemed people of God. A plaque on the ship Nebuchadnezzar has the inscription, “Mark III no. 11,” which seems to be a cryptic reference to Mark 3:11: “And whenever the unclean spirits beheld Him, they would fall down before Him and cry out, saying, ‘You are the Son of God!’”

These similarities, however, are only superficial. In The Matrix, the condition from which humans need to be freed is not slavery to one’s personal moral evil; rather, it is ignorance of one’s real identity. Redemption does not lie in being freed from captivity to one’s sinful nature; rather, it is in “waking up” from imposed unawareness of reality: enlightenment rather than regeneration. In this sense The Matrix is not so much a Christian myth as it is a Gnostic gospel.

GNOSTICISM AND BUDDHISM

Gnosticism is a religious tradition with many different schools, from the ancient Manicheans and Hermetic schools to the modern Mandeans and the New Age movement. It is a worldview with roots in the first century and a more organized following and corpus of manuscripts emerging around the second century.

One of Gnosticism’s central tenets is that salvation comes through secret knowledge. Its name derives from the Greek gnosis, which means “knowledge” or “understanding.” This knowledge is not intellectual or abstract; rather, it is liberating or redeeming. This gnosis usually refers to an esoteric revelation to “chosen” individuals of humanity’s “inner spark of divinity.” Humankind’s problem is ignorance, lack of awareness of its true identity.7 The Gnostic Gospel of Philip proclaims, “Ignorance is a slave, knowledge (gnosis) is freedom” (2.3.84).8

The Matrix is a Gnostic Christ myth. It mixes together elements of the Christian messianic narrative with the pagan Hellenism of Greece, and it throws in a little Orientalism to spice things up. The essence of Gnosticism is syncretism, a parasitic reimagining of Christianity by melding it into pagan mystical musings. Scholar Kurt Rudolph writes of the Gnostic tradition, “It frequently draws its material from the most varied existing traditions, attaches itself to it, and at the same time sets it in a new frame by which this material takes on a new character and a completely new significance….To this extent Gnosis is a product of Hellenistic syncretism, that is, the mingling of Greek and Oriental traditions.”9

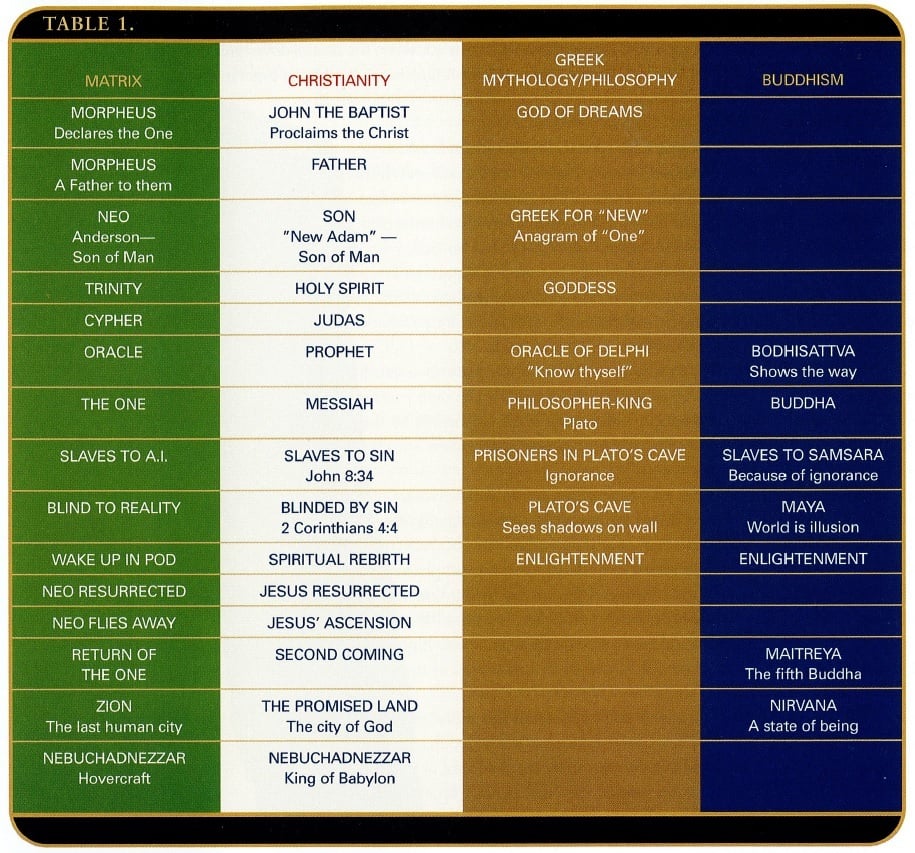

A closer look at The Matrix reveals a plethora of Greek and Oriental ideas that are equally as integrated into the story as are Christian ones: Morpheus is the name of the Greek god of dreams; the inscription “Know Thyself” on the Oracle’s wall plaque matches the inscription on the Oracle of Delphi in ancient Greece; taking the red pill is akin to enlightenment in both Gnostic and Buddhist worldviews; ignorance of, and bondage to, the Matrix is an allegory for the ignorance and bondage spoken of in Plato’s Cave metaphor or the Buddhist concept of slavery to Samsara (the wheel of life, death, and rebirth) as well as “maya” (the empirical world as illusion). Table 1 compares the Christian, Greek, and Buddhist ideas that were blended together in the first Matrix film to produce this Gnostic hybrid.

RELOADED SYMBOLS

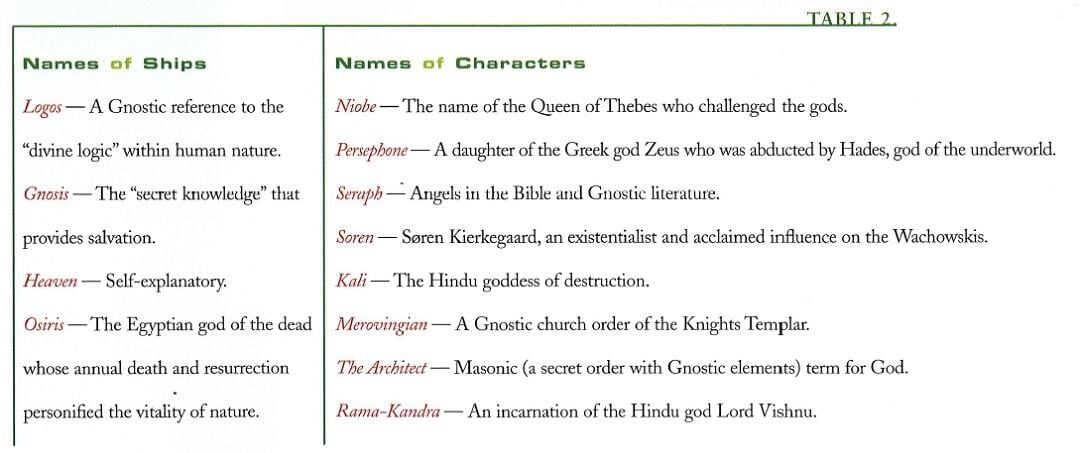

In the sequel, Reloaded, Christian symbolism seems to submerge into Gnosticism. Neo wears a black coat reminiscent of the frocks worn by Roman Catholic priests, and Agent Smith uses language that harkens to the Gospel of John when he states that “Neo set me free.” There’s even a reference to Neo being the “beginning and the end” (Alpha and Omega) of Zion. Zion, it turns out, bears more resemblance to a pagan polis than the holy city of God. The people gather in a cavern called “the Temple,” where speeches are called “prayers” and where everyone takes off their shoes, presumably because of holy ground. Their erotic rave dance, however, intercut with a scene of Neo and Trinity fornicating, portrays elements of a Dionysian orgy rather than the holy church of Christ at worship. The names of people, places, and things in Reloaded bear a greater Greek influence, although other influences continue to be evident (see Tables 1 and 2).

In Revolutions, most of the characters are carried over from the previous film, and little is new philosophically. There are several references to Neo as “savior” and “messiah”; however, the Christ similes are reimagined in terms of an Eastern or Hindu worldview. One new character, Sati, bears the name of a goddess who married Shiva, the destroyer/restorer deity in Hinduism. A reference to “karma,” the Eastern view of a person’s actions determining his or her fate, appears in one of Neo’s discussions.

GNOSTIC REDEEMER VERSUS JEWISH MESSIAH

Gnosticism is known for its “redeemed redeemer” myth; that is, the Savior was himself imprisoned or asleep in ignorance and needed to be awakened to his own divinity before he could help awaken others.10 The Gnostic gospels declare, “He [Christ] who was redeemed, in turn redeemed others” (Gospel of Philip 2.3.71);11 “Even the Son [Jesus] himself, who has the position of redeemer of the Totality, needed redemption as well” (Tripartate Tractate 1.5.125).12 Neo, likewise, must be awakened by taking the red pill Morpheus offers him. We see Neo struggle with his identity through the entire first movie. He doesn’t know whether he is “the One” prophesied to bring salvation to Zion.

The biblical Messiah, however, knows exactly who He is. Jesus, even as a youth, understood His special status as God’s only Son and hinted at this to His own parents (Luke 2:49). He was attacked precisely because of the clarity of His claims to be the incarnation of God Himself (John 8:54–59). Poor Neo may not have known who he was, but Jesus sure did.

When Neo finally is enlightened, he is endowed with supernatural abilities of manipulating the Matrix as well as overcoming the powerful sentient gatekeeper programs. Neo is redeemed from his imperfection of ignorance and can now redeem others. This is in stark contrast to the biblical notion of Christ, who was prophesied to be perfect and without need of redemption Himself: “For it was fitting that we should have such a high priest [Jesus], holy, innocent, undefiled, separated from sinners and exalted above the heavens; who does not need daily, like those high priests, to offer up sacrifices, first for His own sins, and then for the sins of the people” (Heb. 7:26–27).

Another aspect of the Gnostic redeemer myth in The Matrix is the notion of Christ as merely a model of self-salvation. The Gnostic redeemer, like a Buddha, can only show the way of enlightenment; he is not himself the way, the truth, or the life. Salvation through self-knowledge is from within, not from without. This is emphasized forcefully in Reloaded when a grateful boy praises Neo for finding him. Neo responds, “I didn’t find you. You found me.” The boy replies, “You saved me,” and Neo retorts, “You saved yourself.”

When Jesus told the prostitute who washed His feet, “Your faith has saved you” (Luke 7:50), He didn’t mean what Neo meant. The effectiveness of the woman’s faith was in the object of her faith (Christ, and through Him, God), not in the subject (herself). Jesus was adamant that redemption came from outside a person, not from within (John 6:44; cf. Eph. 1:4–5, 11). In contrast to Neo’s reluctance to find and save, Jesus explained to His disciples that He came “to seek and to save that which was lost” (Luke 19:10). The biblical Redeemer saves sinners who are helpless and cannot save themselves (Rom. 5:6–8), the Gnostic redeemer merely illumines the way for the uninitiated to save themselves.

Finally, the contemporary Gnostic notion of Christhood is that it is an office filled by many individuals rather than the distinctive title of only one individual, namely, Jesus. The idea of numerous messiahs reflects the New Age/Eastern belief in multiple Buddhas, avatars, or ascended masters through history, who bring deliverance to their people. In Reloaded, “The Architect” of the Matrix tells Neo that he (Neo) is merely one of six “Ones” so far, who are each essential to the cyclical destruction and rebuilding of Zion. The original Matrix was too perfect to supply the misery needed by humans, so he (the Architect) added the element of choice, which turned out to be a “fundamental flaw” that created an “escalating probability of disaster.” Neo, and the other “Ones” before him, keep the system in balance and stave off total destruction of life on earth by reinserting the prime program of the Matrix into “the source” and restarting Zion each time it is destroyed.

This scene of esoteric gobbledygook from the Architect is a virtual citation of passages from the Nag Hammadi Library of Gnostic texts: “The world came about through a mistake. For he who created it wanted to create it imperishable and immortal. He fell short of attaining his desire. For the world never was imperishable, nor, for that matter, was he who made the world. For things are not imperishable” (Gospel of Philip 2.3.75).13

Kurt Rudolph explains the Manichean version of this Gnostic belief: “A heavenly being (the son of God or of ‘Man’) falls into darkness and is there held captive, and can return again only after leaving behind some part of his being; this part forms the soul of light scattered in the world of the body….To this end, the Father sends his son (Christ) that he may show the (fallen) aeons the way to their origin and to rest. This is tantamount to the dissolution of the cosmos.”14

In The Matrix, the redeemer is a role played by multiple people who provide cyclical creation and destruction in order to maintain equilibrium. Neo seeks “the source” like the Gnostic aeons seek “the origin.” Neo leaves a bit of his “code” in Agent Smith and in the world to which he returns again and again, like the Gnostic redeemer leaves a bit of himself in the world for repeated regeneration. The biblical Redeemer, on the other hand, is a single person who uniquely fulfilled Old Testament messianic prophecies and whose purpose is to save His “chosen ones” from eternal destruction and bring history to its consummation. Creation, fall, redemption, new eternal creation — Genesis to Revelation presents a history of the cosmos that is linear rather than cyclical. “For there is one God, and one mediator also between God and men, the man Christ Jesus” (1 Tim. 2:5, emphasis added).

Revolutions recycles the Christ imagery, but with a reloaded definition. In this film, Neo is referred to as “savior” and “messiah.” At the end, Neo’s final death results in a burst of light in the shape of a cross. He lays his body out in the form of a crucifix in the real world, as he dies battling Agent Smith inside the Matrix. The Source, now displaying itself as a large godlike Wizard of Oz face, simply says “It is done,” an obvious reference to Christ’s own words of atonement on the cross, “It is finished!” (John 19:30). The similarity, once again, is superficial. As we’ve seen, in The Matrix and Gnosticism, “the One” is merely an office filled by many in an eternal cyclical recurrence (see the section on Nietzsche below). In the Bible, “the One” means “the one and only” — mission accomplished in a once-for-all sacrifice (1 Pet. 3:18). “It is finished” means Christ obtained eternal redemption, which forever saved His people (Zion) from their sins (Heb. 9:12; cf. Matt. 1:21).

PURPOSE AND CHOICE

The theme of the first Matrix film is the questioning of our understanding of reality. The theme of the second film, Reloaded, is an equally dense philosophical issue: determinism versus free will. From the start of the first film, Morpheus expresses his undaunted belief in a determinism that somehow is guiding the universe. He trusts the “prophesies” about “the One” even when others around him do not. In Reloaded, he reiterates his faith when he declares, “There are no accidents. We have not come here by chance….I do not see coincidence. I see providence. I see purpose. I believe it is our fate to be here. It is our destiny. I believe this night holds for each and every one of us, the very meaning of our lives.” In this one soliloquy, he uses just about every word used in the debate between determinism and indeterminism: accidents, chance, coincidence, providence, purpose, fate, and destiny. Morpheus never states what he believes to be behind this sovereign control of the universe — personal deity or impersonal fate. There are, however, two ironies to his evangelistic zeal.

First, the very “One” who Morpheus believes will save Zion, namely Neo, does not himself believe in determinism. Neo states in the first movie that he doesn’t like the idea of not being in control of his life. Neo maintains in the sequel his belief in free agency when he argues for the ultimacy of human choice with the Oracle, Merovingian, and even the Architect. His conviction that “everything begins with choice” reflects an existentialist view of human will as being free from all external or internal controls. In existentialism, we exist first, and then we create our essence — who we are — through our choices. Morpheus, ironically, is preaching the predetermined destiny of an individual who himself is preaching absolute free will.

The second irony of Morpheus’s determinism is that the enemy — as embodied in Agent Smith, the cursing Merovingian, the Architect, and other programs — agrees with him. They, too, believe in purpose and destiny, but they are material reductionists. According to this paradigm, all transcendent or spiritual concepts like personhood, free will, and love are reducible to material or physical causes.

The Oracle tells Neo that all stories about ghosts and angels are merely systemic assimilations of hacker programs (such as the déjà vu of the cat in the first movie). Spiritual transcendence is reduced to a series of programs hacking programs. The Architect reveals that even Neo, who believes he is free, is actually “the sum of a remainder of an unbalanced equation inherent in the programming of the Matrix.” Everything is reducible to mathematical formulas, even the so-called savior who is supposed to bring freedom.

The French Merovingian (a possible reference to the French rationalist René Descartes) puts it rather succinctly: “You see, there is only one constant. One universal. It is the only real force: Causality. Action, reaction; cause and effect….Choice is an illusion, created between those with power and those without….Causality. There is no escape from it. We are forever slaves to it.”

Agent Smith clarifies this reductionism with a vengeance: “We’re not here because we’re free. We’re here because we’re not free. There’s no escaping reason. No denying purpose. Because as we both know, without purpose, we would not exist. It is purpose that created us, purpose that connects us, purpose that pulls us, that guides us, that drives us. It is purpose that defines us, purpose that binds us.”

In a strange twist of perspective, the very purposefulness on which Morpheus hangs his hope for freedom is claimed by the computer programs to be another system of control. In fact, the very prophecies Morpheus believes in come from the Oracle, who is actually a program herself. The entire religious symbolism of prophecy and transcendent purpose are ultimately understood in terms of computer programming and mathematical inevitability. Religion in The Matrix is reducible to scientific facts.

NIETZSCHE AND SUPERMAN

Another influence on the philosophy of The Matrix is the infamous nineteenth-century grandfather of postmodernism, atheist philologist Friedrich Nietzsche. The confusion of free will and mechanistic determinism that is set up in the trilogy is reflected in Nietzsche’s own surrender: “Everything here is necessary, every motion mathematically calculable….The actor himself, to be sure, is fixed in the illusion of free will….The actor’s deception regarding himself, the assumption of free will, is itself part of the mechanism it would have to compute.”15

To Nietzsche, it should be noted, this mechanistic world of cause and effect is itself a fiction, created by the prejudice of our senses, blinding us to the “dynamic quanta,” which is the flow of energy in conflict with others in a “will to power.”16 Andy Wachowski sheds light on this dialectical tension when he declares, “We’re giving them causal ties to a mechanistic world and to its dynamic quanta.”17 The Wachowskis are self-professed Nietzscheans, even admitting that he is the key to understanding their Matrix films. In a rare interview, they state: “It’s all there in Nietzsche, man. We dwell in the dominion of truth and are marshalling our armies of metonyms and anthropomorphisms into our future work.”18

Nietzsche, the grandfather of postmodernism, espoused a view that proclaimed the death of God and a meaningless universe of causality, wherein we cannot know the difference between truth or illusion. We are epistemic slaves. The heroic “superman” transcends this nihilism by creating his own meaning and purpose, his own values. Nietzsche called his approach “philosophizing with a hammer” (a possible origin for the name of the Zion ship “The Hammer”). In a sense, Neo is not so much a Christlike savior as he is a superman model for humanity, the one who overcomes his own humanness and in effect becomes his own god, defying the conventions of our Matrix-bound perspectives.

In Nietzsche, there is no knowable reality, just the metaphors, metonyms, and anthropomorphisms of imagined reality to which the Wachowski brothers allude.19 Language is a tool of manipulation for our “will to power” over others. Multiple perspectives (worldviews) fight for control of the culture. Language and its claims of truth do not refer to an objective reality (the “thing-in-itself”), but rather to poetically embellished simulations of one’s view of reality and truth,20 or, as postmodernist Baudrillard would replay it, a copy without an original.

EMERGENT EVOLUTION

The Architect reveals that Neo is merely a programmed anomaly whose “purpose” is to help rebuild a destroyed Zion. He announces an interest in how different Neo is from his five predecessors. The previous “Ones” were programmed with a generic attachment to the human race, but Neo has developed a specific reaction of love for Trinity. This love, the Architect explains, is reducible to “chemical precursors that signal the onset of the emotion,” which suggests the theory of emergent evolution.

This neoevolutionary idea of consciousness emerging out of natural processes or the inherent properties of matter is also called “self-organization.” It was influenced by the naturalism of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and has been updated in recent times.21 It is a reduction of consciousness, spirit, or identity to physical properties. Human consciousness is not truly spiritual, but simply the result of increased physical complexity in an organism or system. As an organism “evolves,” it becomes more complex, and out of that complexity emerges a “consciousness.” This self-consciousness then creates a system of linguistic symbols (known as religion) to justify its perceived transcendence, misidentifying otherwise unknown natural causes as supernatural.

According to this view, the religious fervor of those like Morpheus is really a misinterpretation of the actual underlying reality of mathematical formula (the ancient Greek Pythagorean belief that “all is number”). Humans are ultimately evolving machines whose consciousness is not part of their being created in the image of a transcendent personal God, but rather a trait that magically occurs through increased complexity of material organization.

This self-organizing theory of matter is the unscientific premise behind some artificial intelligence theory. It is also an idea that is carried out further in Revolutions. Neo’s consciousness is trapped in a train station at Mobil Avenue (an anagram of limbo), between the two worlds of reality and the Matrix, where he is reacquainted with Rama-Kandra and his wife and child. It is here that Rama-Kandra, the Indian (read: Hindu) “program,” reveals to Neo that theirs is the first program child born free in the Matrix. Rama-Kandra and his wife, Kamala, have developed a love for their offspring that inspires them to sacrifice themselves for her as “the last exile.” When Neo asks how a program could “love,” Rama-Kandra explains that love is merely “a word. What matters is the connection the word implies.” What matters is that humans invest words with meaning. Transcendent notions like love and freedom are merely functions of language, and language is a program, a social construct. So why can’t a highly complex program (the material) evolve to the level of experiencing “love” (the immaterial) since humans, as highly complex, evolving, material organisms, do the same?

Agent Smith tells Neo that freedom, truth, and love are delusions, “vagaries of perception. Temporary constructs of feeble human intellect trying desperately to justify an existence that is without meaning and purpose. And all of them as artificial as the Matrix itself. Although it’s only a human mind that invents something as insipid as love.” Even the godlike floating head at the climax of Revolutions is called Deus Ex Machina, which means “God from the Machine,” another Greek reference to transcendence arising from materiality.

The problem with these evolutionary ponderings lies in their materialist/naturalist assumptions. If transcendence is reducible to highly organized information, mathematical formulas, or chemical and physical causality, then Agent Smith and the Merovingian are right: there is no freedom, only the illusion of it. Charles Darwin himself wrote, “The horrid doubt always arises whether the convictions of man’s mind, which has developed from the mind of lower animals, are of any value or at all trustworthy. Would anyone trust the conviction of a monkey’s mind, if there are any convictions in such a mind?”22

Put simply, the belief that everything is reducible to material cause and effect is itself not reducible to material cause and effect. Materialism refutes itself. In order for rationality to be intelligible, it must be immaterial, transcendent, and objective; it cannot be reducible to material causality. C. S. Lewis asserted, “Unless human reasoning is valid [beyond material causes], no science can be true.”23 That includes the science of The Matrix.

UNITY OF OPPOSITES

It appears, however, that irrationality is not considered an ultimate problem to the creators of The Matrix. In Revolutions, one of the dominant themes seems to be the unity of opposites, an Eastern dogma of yin and yang (note the earrings on the Oracle). In this view, opposing aspects of reality balance each other out in a harmonic convergence of existence. The metaphysical tension set up in The Matrix (illusion versus reality), and intensified in Reloaded (freedom versus determinism), is resolved in Revolutions as a universe of rational and irrational counterbalance. This Hindu metaphysic rounds out the multicultural bricolage of theology in the trilogy. The Merovingian explains that where some see coincidence, he sees consequence, and where some see chance, he sees cost. He muses that the pattern of love is similar to the pattern of insanity. “Love,” the driving force of humanity, is an irrational creation that gives us meaning in a meaningless universe (shades of Nietzsche). That irrational love is what Trinity says matters the most before she dies in Neo’s arms.

The Oracle elucidates to Neo that her own purpose is to unbalance the equation created by the Architect and to reinforce that tension of the irrationality of choice in a determined world. She describes Agent Smith as Neo’s “opposite,” his “negative,” the yin to Neo’s yang. The grand finale is a one-on-one battle between supermen Smith and Neo. Smith asks why Neo persists in fighting a losing battle, to which Neo replies, “Because I choose to.” At the end of the day, in a causally determined universe, the superman still chooses, irrational though this proposition may be. We see Smith become one with Neo, as he transforms Neo into another Smith, but that metamorphosis ends up destroying the viral Smith and all his replicated minions, bringing harmony back into the Matrix. Then the dead Smith further transmutes into the Oracle. In Nietzschean terms, Dionysus (the god of freedom and chaos) triumphs over Apollo (the god of reason and order) through sheer will to power that ends in a union.24 “The One” meets the anti-One and all is ultimately unified — just as the Architect foretold.

The philosophical tension created by rational/irrational, material/immaterial, freedom/determinism dialectic is supposedly resolved in an irrational synthesis or unity of contradictions typical of Eastern and Gnostic philosophies. Humanity somehow chooses freely in a causally determined universe. Purpose is somehow created in a meaningless existence. Humanity is somehow both ultimate and nonultimate. In my view, however, this philosophical tension is unresolvable given a materialistic starting point and leads to the unintelligibility of such non-Christian worldviews. Philosopher Greg Bahnsen explains,

The various schools of philosophy set forth by unbelievers cannot explain man’s personal and intellectual freedom in a mechanical world. They cannot provide for a reliable connection between the mind and its objects — or the mind and other minds. They cannot escape the egocentric predicament, subjectivism, and relativism…. [W]hen the unbeliever begins philosophizing with himself at the center, he ends up unable to escape himself (subjectivism); and since every unbeliever faces the same dilemma, nobody can speak with authority about objective reality for anybody else (relativism)….In short, the unbelieving worldview renders personality, self-consciousness, mind, logic, science, and morality unintelligible.25

This unintelligible confusion of contradicting worldviews is probably why the Matrix trilogy concludes with a faith-oriented focus. In Revolutions, just about every major character from Morpheus to Niobe has a moment when he or she expresses “belief” in either Neo or the salvation of Zion. The little boy who saves the dock by blasting open the gate yells, “I believe!” just before he pulls it off. The final words of the film are reserved for the Oracle who, when asked by Seraph if she always knew how it would end, replies, “No. No, I didn’t. But I believed. I believed.” Belief and love, therefore, are the ultimate hope in the Matrix universe of rational determinism versus irrational human choice and freedom.

The Nietzsche quote at the top of this article articulates that the goal of postmodernists like the Wachowskis is to use the dominant mythology and language symbols of a herdlike culture in a subversive way; to redefine those symbols; to “lie” to the ignorant masses by using their religious metaphors and investing them with new meaning. The Wachowski brothers, unfortunately, are not so helpful or forthright in explaining their intent and philosophy behind the Matrix story, as they tend to avoid most publicity, thus fulfilling Nietzsche’s own aphorism that good storytellers are often bad explainers.26 It’s a sure bet, however, that they are philosophizing all the way to the bank.

NOTES

- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Portable Nietzsche, trans. Walter Kaufmann (New York: Viking, 1954), 47.

- Joseph Campbell with Bill Moyers, The Power of Myth (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 39.

- See the Philosophy section at <http://www.whatisthematrix.com>.

- Steven Connor, Postmodernist Culture: An Introduction to Theories of the Contemporary (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1997), 134.

- David Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change (Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1995), 289.

- All Bible quotations are from the New American Standard Bible.

- Kurt Rudolph, Gnosis, trans. and ed. Robert McLachlan Wilson (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1985), 55–57.

- James M. Robinson, ed., The Nag Hammadi Library in English (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1988), 159.

- Rudolph, 54.

- Ibid., 119.

- Robinson, 152.

- Ibid., 97.

- Ibid., 154.

- Rudolph, 121, cf. 84.

- Friedrich Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human: A Book for Free Spirits, trans. R. J. Hollingdale (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 57 (no. 106).

- Friedrich Nietzsche, The Will to Power, trans. Walter Kauffmann and R. J. Hollingdale, ed. Walter Kauffmann (New York: Vintage, 1968), 338–39 (no. 635).

- Peter Bart, “Cracking the Wachowski’s Code,” Variety.com, May 25, 2003.

- Ibid.

- Nietzsche, The Portable Nietzsche, 47.

- Ibid., 45–46.

- See Eric Jantsch’s Self-Organizing Universe: Scientific and Human Implications of the Emerging Paradigm of Evolution (St. Louis: Elsevier, 1980).

- Charles Darwin, in a letter to W. Graham (July 3, 1881), quoted in The Autobiography of Charles Darwin and Selected Letters (New York: Dover Publications, 1958; originally published in 1892), quoted in James W. Sire, The Universe Next Door: A Basic Worldview Catalog (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1997), 83.

- C. S. Lewis, Miracles (New York: Macmillan, 1960), 14.

- Nietzsche, Will to Power, 340 (no. 636).

- Greg Bahnsen, Van Til’s Apologetic: Readings and Analysis (Phillipsburg, NJ: Presbyterian and Reformed Publishing Co., 1998), 314–15.

- Nietzsche, Human, 94.