This article first appeared in Christian Research Journal, volume 35, number 02 (2012). For further information or to subscribe to the Christian Research Journal go to: http://www.equip.org

The Hunger Games and its sequels are page-turners, fast-paced and engaging, with characters who are interesting and complex. It is easy to see why the books are popular and why the first book has been made into a film. What’s good news for Christians is that these books are also very useful material for literary apologetics—though perhaps in unexpected ways.

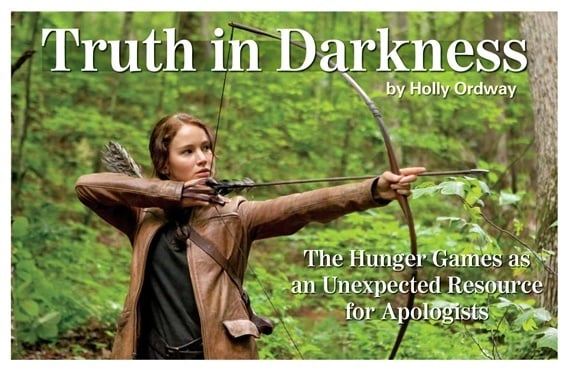

The Hunger Games, by Suzanne Collins, is set in a future United States after a catastrophic war. A totalitarian government (the Capitol) controls the twelve Districts through military power and psychological oppression. Every year the Districts are each required to send two children as tributes to fight to the death in the Hunger Games as a bloody reminder of the futility of rebellion. However, the Hunger Games are not just a cruel means of suppressing dissent: they are also a prime source of entertainment for the citizens of the Capitol. The story of The Hunger Games begins with a sixteen-year-old girl named Katniss who volunteers to go to the Hunger Games (and face almost certain death) in place of her younger sister.

While The Hunger Games and its sequels do not affirm a Christian worldview,1 they are perhaps all the more valuable for apologetics as a result. The “watchful dragons”2 of skepticism are alive and well in the minds of many readers who will simply reject a story with overt Christian elements. One approach is for authors to circumvent those watchful dragons by subtle handling of Christian themes in their work, as C. S. Lewis did; a different approach is for apologists to get past modern dragons by using non-Christian stories to explore the truths of Christianity.

LOOKING FOR TRUTH IN DARKNESS

The Hunger Games is a dark series, filled with death, violence, betrayal, and mistrust. As a result, it is valuable to apologists for its unflinching look at the darker aspects of human nature. The truth is that people do sin and sin has terrible consequences, both individually and communally. Books that avoid or attempt to sugarcoat the problem of evil and suffering will ring false to readers, but a story that confronts the brokenness of the world provides an opportunity to discuss issues of evil that young people may not otherwise feel able to articulate.

The Hunger Games does not come to a Christian conclusion about the problem of evil, but it is still useful for apologetics because of the compelling way that it raises the issues. It is tempting to look for a book that jumps right to the presentation of the gospel, but readers need room to think through issues and engage with them on an experiential and emotional level. The more fully someone has wrestled with the problems of evil, violence, and the absence of God, the more that reader will have a desire for the light of truth.

THE HUNGER GAMES AND VIOLENCE

One of the most immediately noticeable elements of The Hunger Games is its violence. However, as the story unfolds it becomes clear that Collins is in fact critiquing a number of disturbing elements in current culture: violent video games, violent film and television, celebrity culture, and voyeuristic “reality” television shows. Appreciating her critique will allow apologists to make more effective use of the series to challenge young people’s attitudes toward unhealthy entertainment choices.

Media critiques of video game violence have typically focused on a few particularly repugnant games, but what is perhaps more important is that even “normal” action games are often centered around warfare, and with today’s computer graphics, on-screen violence is depicted at nearly film quality. What’s more, the most popular action games today are “first-person shooter” (FPS) games in which the player takes on the role of the soldier. A young person who plays an FPS game regularly is routinely exposed to images of violent death caused by his (or, less often, her) own lethal actions, in an immersive, addictive experience.

The plot of The Hunger Games centers on what is essentially a live-action video game. Readers follow Katniss as she has to kill or be killed in the arena, just as if they were playing an FPS game. If The Hunger Games were to follow secular culture’s entertainment trends, the reader would find the action to be exciting and enjoyable as Katniss bloodily defeats her opponents.

However, Collins subverts the standard video-game narrative. By the time we get to the violent scenes, the reader likes Katniss and knows that she is a girl who has suffered and who fights only to save her younger sister from the same fate. Katniss is tough and resilient, to be sure, and she does kill—but not eagerly. As she goes through the game, the reader also develops empathy for other players in the games, such as the young, sweet Rue. However, only one person will survive the games; all the others must die. The situation overcomes the detachment of the video-game player.

In the second book of the series, Catching Fire, the emotional fallout on Katniss and the others becomes clear. The images of violence from the first book return again and again, but this time as nightmares; Katniss and the other survivors are profoundly wounded. The books move the reader from an easy acceptance of gratuitous violence to a deeper realization of the human cost of casual violence—not by simply asserting the horrors of violence, but by showing it.

In the end, it becomes clear that Collins is not glorifying violence, but rather challenging the current cultural mindset that views violence as entertainment. This is a perspective that can be taken up gladly by the Christian apologist.

One of the ways that an apologist can use The Hunger Games, then, is to lead into a critical discussion of the reality-television/video game/violence-as-entertainment industry as a whole. The Christian apologist can take Collins’s critique considerably deeper, but the value here is that Collins has provided the literary apologist with an engaging story that dramatizes the issues in a compelling way so that readers can make connections that otherwise would be missed.

THE HUNGER GAMES AND THE ABSENCE OF GOD

If the presence of violence is notable in The Hunger Games, equally notable is the absence of God. Nowhere in the books do we get any indication that any of the characters believe in God, let alone the most holy Triune God of the Bible. The idea of immortality of the soul or final judgment is likewise utterly absent from the books. Given that so many characters die in the books, the absence of any reflection whatsoever on what happens after death is itself quite telling. In fact, the setting seems to be an atheist’s dream: religion has simply vanished, but many of the characters are still strongly ethical, dedicating their lives to helping others, caring for their loved ones, and seeking for justice.

Does this mean that The Hunger Games is anti-Christian? Not necessarily.

Apologists working with literature should always be aware of the conventions of genre: in this case, The Hunger Games is science fiction, and specifically a dystopia, or anti-utopia. The genre of dystopia is a form of thought experiment in which aspects of present-day culture are taken to extremes to bring the dangers of the present day into clearer focus.

The main dystopian elements in The Hunger Games are the totalitarian government and the use of entertainment media to keep the citizens under control, but the total absence of religion or any awareness of the spiritual world may be another dystopian element. Whether or not Collins intended the subtle atheism of the world of The Hunger Games to be a critique, as a good writer she explores the consequences of ideas and depicts them in the stories for readers to think through.

What is missing in this fictional world is transcendence: the characters have no sense of a supernatural reality over and above the physical, no grounding for moral judgments, and no firm basis for happiness. In the third book, Mockingjay, the absence of a grounding for morality becomes a pressing issue. Katniss feels instinctively that some of the weapons and military tactics used by her friends in the rebellion cross a moral line, yet she is unable to articulate any argument against them. What would a Christian be able to say in her place?

Collins is an honest and thoughtful writer: the books show what it means to live in a world in which God exists but is unknown. The characters dimly grope after doing what is right, without knowing why; they yearn for love, beauty, and truth and are frustrated when they cannot find these things reliably in other human beings. The trilogy closes with an attempt at a happy ending, but it has none of the joy of a true happy ending, what J. R. R. Tolkien calls “eucatastrophe,”3 precisely because the joy of eucatastrophe comes from its echo of the gospel; no such joy is possible in The Hunger Games because of its definitive exclusion of the transcendent.

The Hunger Games books do not present arguments against God, but rather depict a world in which He is apparently absent. What is such a world like? Are the New Atheists right in preferring such a world? Is that how the world really is? These questions are both important and frightening.

A SAFE PLACE FOR EXPLORATION

It is possible to have a serious discussion of the theological and ethical issues raised in The Hunger Games, and to challenge the worldview implicitly presented in the series, without attacking the books, downplaying the value of what Collins has done, or condemning the personal connection that readers have formed with the characters.4 Even if the books are simply used to get people thinking about issues of morality, death, and the source of ultimate happiness, they will have served a valuable purpose for apologists.

Recognizing the Christian God as the ground of all being, of all morality, of all that is good and true can be a shattering experience. Certainly it requires a radical re-envisioning of what it means to live one’s life. In a culture that routinely encourages people to take no heed to what might be beyond the material, it’s all too easy simply to push the big questions aside. One of the strengths of literature for apologetics is that it offers a safe environment for people to explore difficult, life-changing ideas. The dystopian, violent world of The Hunger Games is, paradoxically, a safe place for seekers and apologists to meet to explore the truth claims of theism and Christianity.

Holly Ordway holds a Ph.D. in English from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, an M.A. in English Literature from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and an M.A. in Christian Apologetics from Biola University. She is the author of Not God’s Type: A Rational Academic Finds a Radical Faith (Moody, 2010) and speaks and writes regularly on literature and literary apologetics.

NOTES

- It is important to note that this article does not make any judgment on or evaluation of the personal faith of Suzanne Collins, but simply considers the worldview presented in and through the books.

- C. S. Lewis, “Sometimes Fairy Stories May Say Best What’s to Be Said,” On Stories and Other Essays on Literature (Orlando: Harcourt, 1966), 47.

- J. R. R. Tolkien, “On Fairy-Stories,” The Tolkien Reader (New York: Ballantine, 1966), 71.

- It is difficult to overstate the value of being able to take the story as it is. One of the difficulties in using Stephanie Meyers’s Twilight series for apologetics is that readers identify with Bella (as they do with Katniss), but any serious critique of the series will inevitably end up forcing readers to reject or qualify their identification with her. Most readers will instead defend Bella (and her bad choices). As a result, apologists will find it difficult to communicate their message to the very readers who need to hear it most.